Seimaibuai (noun)

[Say-My-B’eye] [Rice polishing rate]

Japanese characters: 精米歩合(精: pure; 米: rice; 歩合: ratio)

What is Seimaibuai?

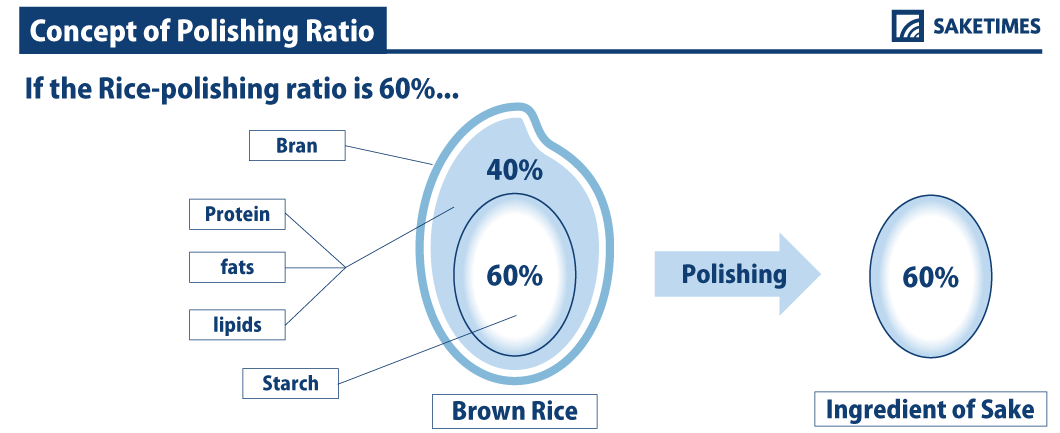

All rice used to brew sake, regardless of type or variety, begins its journey to becoming sake as brown rice — that is to say, as wholegrain rice with its bran layer still intact. From there, rice used to make different grades of sake will go through different degrees of polishing, or milling, that gently and precisely removes the outer layers of each individual grain.

The amount of rice remaining after the polishing process in relation to its original weight – expressed as a percentage – is known as its “seimaibuai,” and is often used as the primary indicator of a sake’s grade. The grade, in turn, largely represents the sake’s overall characteristics.

How Seimaibuai affects sake

Different grades of sake require different seimaibuai. From least to most polished, the grades are: Honjozo (70%), Ginjo/Junmai Ginjo (60%), and the premium Daiginjo/Junmai Daiginjo (50% or less).

In other words, brewing Daiginjo, for example, means breweries lose half of the weight of the rice they paid for even before production begins. And the expenses don’t stop there; it requires time and sophisticated technologies to mill rice to such low seimaibuai percentages. Milling rice to 40% without breaking the remaining core of the grain is a delicate and time-consuming process that takes upwards of 50 hours.

Unsurprisingly, the cost and time commitment associated with brewing a Daiginjo is one of the factors in this premium sake’s higher price tag.

The seimaibuai figures above are only the minimum requirement for a sake to be classified as a certain grade; leading some brewers to cheekily test the extremes, like Tatenokawa Brewery, who created the wondrous 1% seimaibuai Junmai Daiginjo “Zenith” sake last year.

Why do breweries go the costly extra mile of polishing? The outer layers of rice grains house nutritional components like protein and lipids that, when fermented, can create unwanted flavors in the sake. Milling away the outer layers enables brewers to work with the core of the rice grain, called the shinpaku, where the starch is concentrated. Exposing the shinpaku also helps facilitate the growth of koji mold, ensuring an even and thorough propagation essential especially in Ginjo styles of sake.

Moderation is Key

As with many other aspects of sake making, determining the right seimaibuai is a balancing act. While polishing helps create a clear-tasting sake, excessive polishing can strip the sake of character.

Finally, a word about all that “wasted” bran that’s polished away. The powdered byproduct of the milling process is fully repurposed into things like cattle feed, fertilizer, gluten-free flour and even eco-friendly paint. Historically rice farmers by primary trade, even today’s brewers are loathe to waste this all-important grain.

Learn More>>What is the Rice Polishing Ratio?

Free Sake Infographics:Feel free to download and use them freely from here to help you learn more about sake!

Comments