In much of the western world, New Year’s Eve means a wild night out with friends and toasting the stroke of midnight with glasses of champagne. Japanese New Year’s, however, is a very different celebration altogether.

The New Year’s season in Japan is comparable in many ways to a western-style Christmas holiday. Rather than office Christmas parties, in Japan you’ll find bonenkai (year end parties), and in place of Christmas cards, people send nengajo (New Year’s cards). And, instead of ringing in the new year at bars and clubs, many Japanese prefer to spend the holiday with quiet family gatherings.

Days Leading up to the New Year

Like with a lot of major holidays, the days before New Year’s Day in Japan can get hectic.

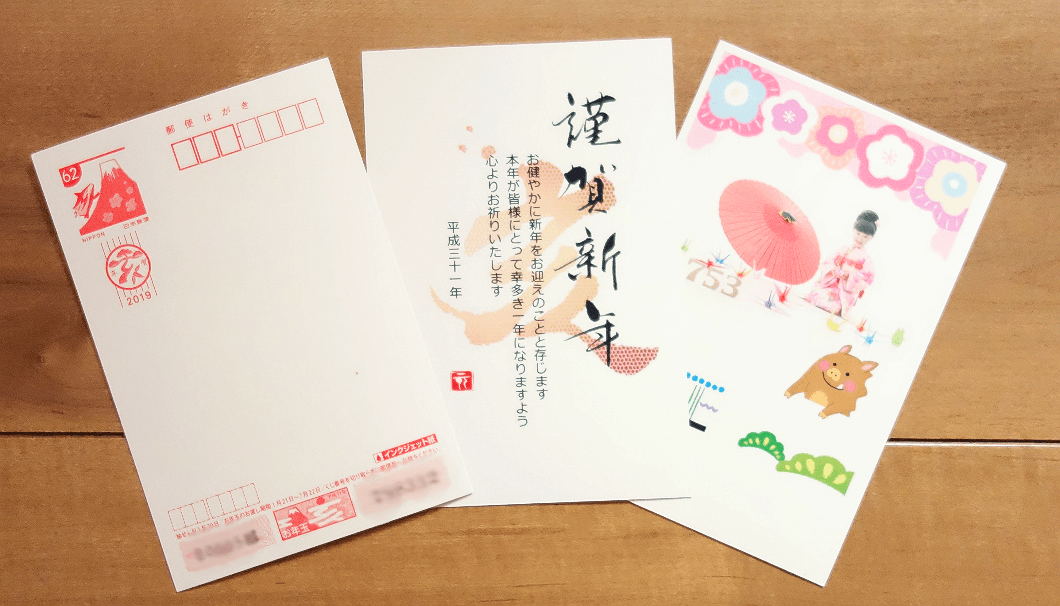

Making nengajo is one of the primary chores facing residents during the season. These small postcards with a New Year’s greeting and picture can be custom-made on a home computer or pre-ordered from a department store or post office. There are even apps available now that help streamline the process.

They often feature the animal of the Chinese zodiac for the coming year. 2019 will be the Year of the Boar.

The custom was once very widespread and fraught with ceremony and potential for faux pas, but it’s been slowly downsizing in recent years, with many opting to send more generic cards or even just text messages to close friends and family.

New Year’s Eve in Japan

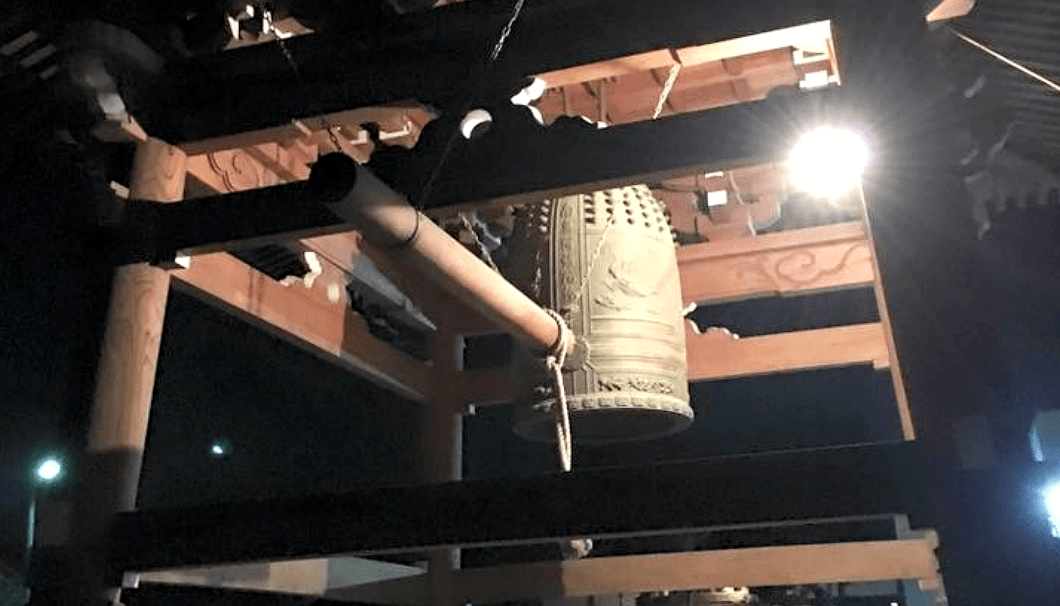

The concept of “New Year’s Eve” isn’t a big deal in Japan for the most part. Celebrations tend to occur on New Year’s Day itself. However, when in the mood, some people like to go late at night to a Shinto shrine and pray or to a Buddhist temple to listen to the bells ring precisely 108 times, starting at exactly midnight.

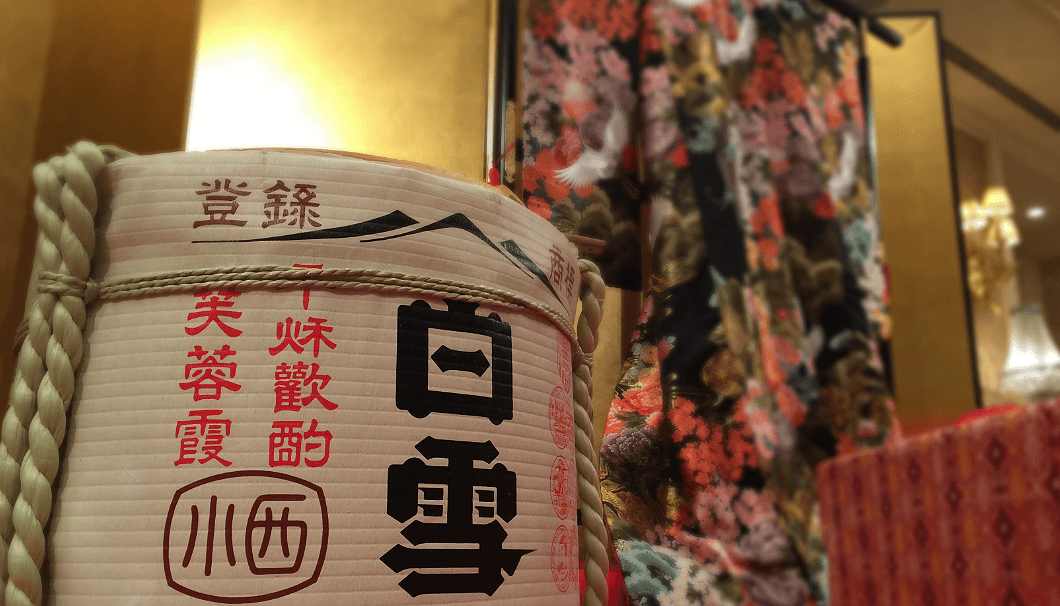

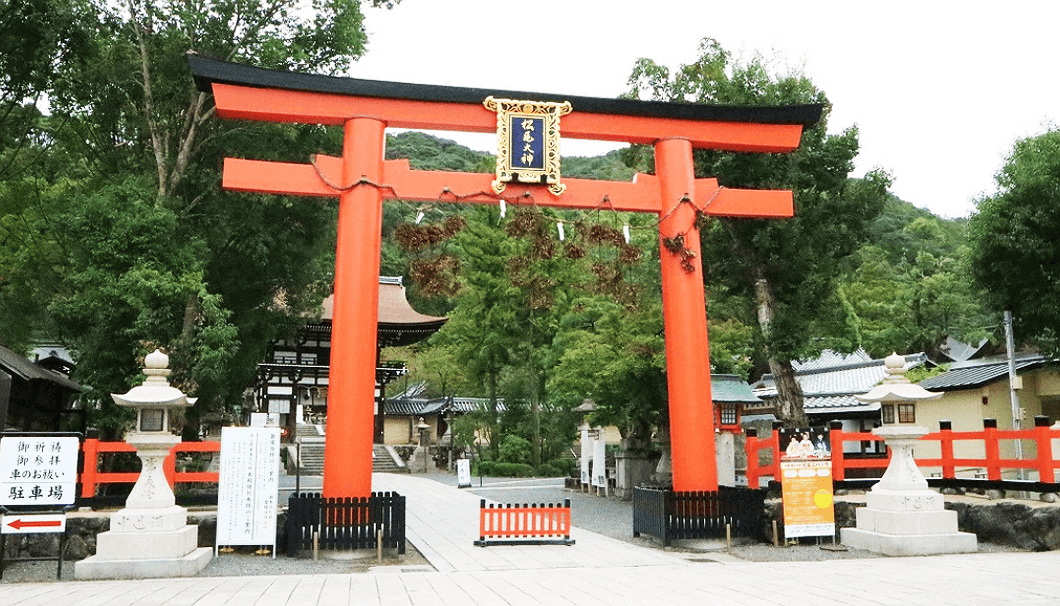

If possible, we’d recommend visiting one of the “Big Three Sake Shrines” in Japan: Omiwa Shrine in Sakurai, Nara; Umenomiya Shrine in Kyoto; or Matsuo Shrine also in Kyoto.

But even if you can’t check these locations out for yourself, many shrines offer sake (sometimes for free!) during New Year’s.These are used for the custom of omiki, in which an offering of sake is made to the enshrined gods, but also drank by the person offering so they can share in the gods’ spiritual power.

Many also purchase omikuji during these ceremonial shrine visits. Guests first pull one of many wooden sticks from a cylindrical box. That stick is engraved with a number that corresponds to a paper, found on a separate shelf, printed with a fortune for the coming year. Fortunes may vary by temple, but usually come in 大吉:daikichi (very lucky), 吉:kichi (lucky), 凶:kyo (unlucky), and 大凶:daikyo (very unlucky). Bad fortunes can then be tied to a rack nearby to leave the bad luck behind.

People tying their omikuji to a rack

People tying their omikuji to a rack

Revelers, by the way, are invited to make their New Year’s Day pilgrimage up to a few days later if they choose – a modern convenience designed to keep the most popular shrines and temples from getting overcrowded.

Another New Year’s Eve activity is to take part in the custom of hatsunihode – watching the year’s first sunrise. Some say it’s good luck, but mainly it’s an opportunity for meditation on the year ahead. It’s generally done in a scenic place like a mountaintop, or ideally a location where you can see the sun rise over Mt. Fuji.

New Year’s Day in Japan

Family gatherings are the most common of New Year’s Day celebrations and include large dinners and lots of drinks. More traditional homes will prepare a home-cooked osechi meal: a large, often multi-tiered box of various foods, each with a specific significance.

For example, many foods like kamaboko (boiled fish paste) and shrimp are colored red, it’s said, to repel evil. Yellow foods like kazunoko (herring roe) and kurikinton (sweet chestnuts) are symbolic of wealth. The foods’ characteristics are also symbolic, such as the shrimp’s bent over figure representing a wish to reach old age. Likewise, tough, fibrous burdock root represents strength.

Nowadays, it’s not uncommon for families to have their osechi catered. Most supermarkets offer osechi preparation services, which can cost around 30,000 to 50,000 yen (US$260 – $440). Some families might even just skip the osechi altogether and make their own feast.

If you have the opportunity to spend New Year’s with a Japanese family, greeting them each individually with “Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu” will be well-received, as it’s a roughly equivalent sentiment to “Happy New Year.”

Chances are drinks will be flowing steadily during New Year’s gatherings, too. Whether it’s sake, beer or wine, Japanese custom dictates that people pour each others’ glasses whenever they notice a companion needs a top-up.

It’s a pretty simple custom to get the hang of, but be warned: the constant top-ups can easily lead to consuming more than you intended. If you’re afraid of overindulging, be sure to nurse your drink and when you’ve had enough, just leave your cup full until it’s time to go.

Toso, the Sake of New Year’s

Toso, short for tosoenmeisan, is a sake infused with medicinal herbs. There are many kinds of toso, each with their own purported health benefit, but for the most part they’re said to help bolster drinkers against the common cold and ease upset stomachs.

Toso is traditionally served in red lacquer

Toso is traditionally served in red lacquer

For hundreds of years, Japan has had the custom of drinking toso on the first day of the year. Though it was once exclusive to the nobility, in the Edo period the practice became widespread. It’s said that a few gulps of toso ensure health and happiness for the year to come.

Don’t let the “medicinal” label fool you, though. Toso can be drunk like any other sake. And since its considered good for your stomach, it can serve as a nice counterbalance to the osechi meal’s bountiful fare.

Into the New Year

With family obligations out of the way, a great way to spend your remaining days off is to go shopping. The post-New Year season is one of the biggest shopping times in Japan with nearly all major brands and stores offering fukubukuro “lucky bags”.

These are large bags of assorted items, usually sold at a discount. Traditionally they were meant to be secret, but nowadays the contents are usually known before buying. Nearly any manner of retail product can be found in a fukubukuro, from electronics to fashion items, and sometimes even sake.

With a belly full of food and sake, a lucky fortune in your pocket, and a bag full of your favorite swag, you’re all set to tackle the year ahead in Japan. But no matter where you are in the world and however you choose to celebrate the new year, Sake Times wishes you all the best in 2019!

Comments