Barrel Buddies

Although now almost entirely replaced by steel tanks, the fermentation of sake was once conducted in large wooden vats. Because of the strict desire for specific conditions when making sake, vessels could only be used for about 30 years before they degraded too much to continue being used for their intended purpose. When they could no longer maintain the needed purity, they were sold off to soy sauce makers.

But that wasn’t the only thing that changed hands between these two types of producers. Sake brewers themselves would also occasionally cross over into soy sauce production and vice versa.

This could be seen in Hyogo Prefecture in the traditional brewing songs of Tatsuno City’s soy sauce producers and sake breweries in nearby Tamba City. Aside from some minor differences, these historical songs have almost identical lyrics.

The extent of sake brewing’s influence on soy sauce production isn’t entirely clear, but how these products are made today clearly belies significant crossover.

Would a Mold By Any Other Name Taste As Sweet?

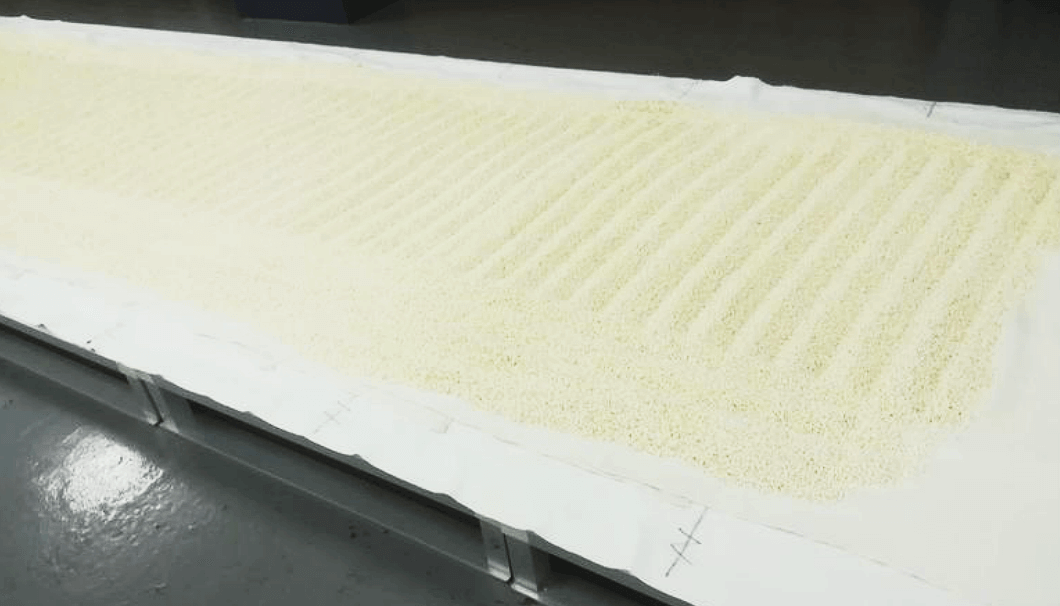

The main ingredients of sake and soy sauce are fundamentally different, with sake coming from rice and soy sauce being made from soybeans. But, both use a special type of mold called koji as the active ingredient in fermentation. Sake largely relies on Aspergillus oryzae to begin converting starch into sugar to create a white-colored mixture called “rice koji”.

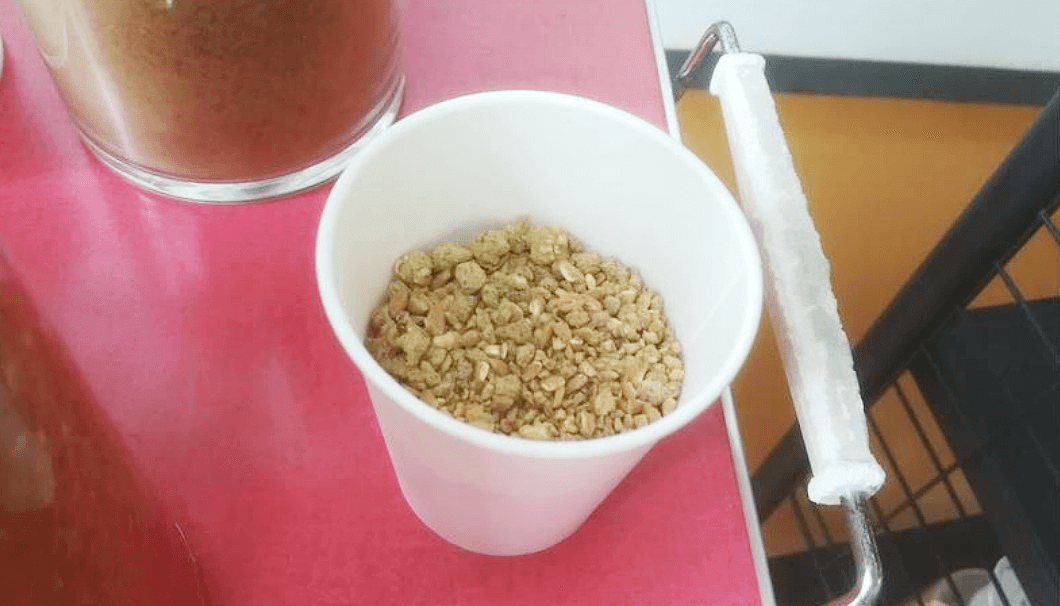

Soy sauce, on the other hand, employs Aspergillus sojae and roasted wheat that acts as a catalyst to create the brown “soy sauce koji.”

Rice and soy are steamed and boiled, respectively, and propagated with koji mold to create an active mixture called “moromi”. One major difference here is that salt water is used for soy sauce whereas freshwater is added to the rice koji for sake.

The salt water not only steers the taste of soy sauce in a different direction, but it helps to weaken the production of alcohol through fermentation. In sake fermentation, the rice’s starch is converted to sugar, which is then converted to alcohol. This occurs with the wheat component of soy sauce fermentation as well, but that is relatively minor compared to the amino acids which are derived from the protein in the soybeans.

This balance creates the savory flavor, deep brown color, and low alcohol content – and yes, soy sauce is technically alcoholic! – that soy sauce is known for.

Despite these differences in ingredients, the process of converting raw material to a semi-fermented mash using a specific variety of mold takes place for both sake and soy sauce. This similarity continues in the remaining steps of their creation.

Sake Springs, Soy Sauce Falls

Sake and soy sauce are both fermented throughout the winter months, but sake stops in the spring to begin squeezing out sediment before pasteurizing, aging, and bottling. Soy sauce, on the other hand, remains in the fermentation phase for a total of ten months on average before the squeezing takes place around autumn.

Soy sauce can be aged in the tank for longer periods of time, but after squeezing it’s best to bottle it right away. Further aging at that point will likely result in a bland, oxidized sauce.

The squeezing process of soy sauce is physically harsher than that of sake, and as a result the remaining sediment, known as lees, is thinner and dryer. While a variety of uses for sake lees have been developed over the years, from skin care products to cooking, soy sauce lees is much too dry and is generally reserved for cattle feed.

Once the finished product is bottled, both soy sauce and sake – two distinct yet symbolic elements of Asian cuisine – are distributed to store shelves.

There they are bought up by a public largely unaware that these liquids with vastly different properties have actually come from strikingly similar origins, developed through a shared history.

Comments