Cloudy Sake

Nigori is a white, cloudy style of sake. The name, in literal terms, even means “cloudy.” Although often described as “unfiltered,” this isn’t strictly true, since Japanese law stipulates that all true sake must be filtered. Clear sake gets that way through a process of pressing the mash through a cloth sieve. Nigori, though, follows all the same processes but is simply passed through a more porous cloth. This allows bits of rice solids to remain in the liquid, giving nigori both its appearance and name.

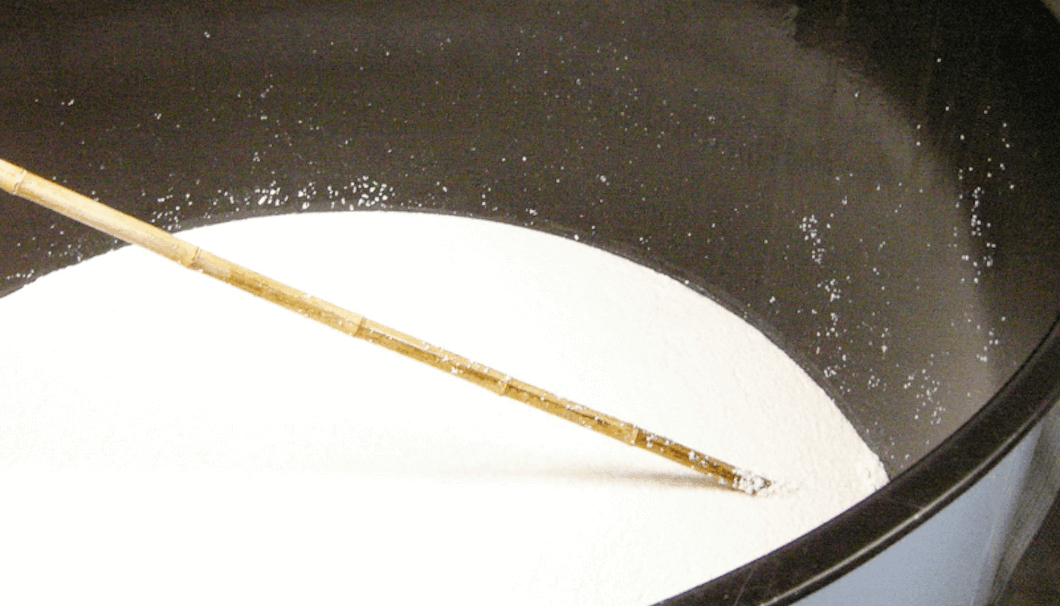

Funashibori pressing process – mash is bagged in small cases made of cheesecloth-like fabric and gently squeezed to yield clear sake.

Funashibori pressing process – mash is bagged in small cases made of cheesecloth-like fabric and gently squeezed to yield clear sake.

Drinking Nigori

Nigori is characterized by a creamy texture and a mild, sweet taste. It pairs well with desserts or spicy dishes. It should be served chilled, and once opened, it’s best kept on ice between pours. Nigori is also a great base for cocktails!

Banned Homebrew

Doburoku is a traditional Japanese homebrewed concoction. Japanese law has actually banned making the stuff since the Meiji era introduced measures regulating the production and taxation of alcohol.

Doburoku has a lower alcohol content than other sake. In the normal sake brewing process, the main ingredients – steamed rice, koji, and water – are not added to the shubo (starter mash, also known as moto) all at once, but in batches over the course of several days. This gradual process, taking place in a controlled temperature environment, keeps the yeast producing alcohol, and the brewer decides when fermentation stops.

Making doburoku, though, calls for adding everything in one go. Thus, the yeast in the shubo doesn’t have time to multiply as much as it would in a normal batch. As the koji breaks down the starches in the rice, in this case, the yeast becomes overworked by the sheer volume of sugar created. The amount of yeast produced is simply not enough to convert much of the sugar to alcohol. The sugar is then allowed to naturally kill off the yeast, which stops the fermentation process at a much earlier stage of brewing. The result is a sweeter drink with a lower alcohol content.

Homemade doburoku at Makoto-ya

Homemade doburoku at Makoto-ya

Doburoku is rarely brewed in Japan nowadays seeing as it’s technically banned without a specialized license. Most of these licenses are granted to Shinto shrines, but also to some Japanese inns and restaurants who make it from their own rice. These brewing venues are designated as “special wards” for small-batch (less than 6 kl a year) production. Rice farmer Shinichi Kobori, for example, produces his own doburoku, which he serves at Makoto-ya, his sushi restaurant in Katori, Chiba. And at Nihonshu Hotaru in Tokyo’s Kanda neighborhood, Tomiomi Miyai brews and serves his own doburoku by the glass. These purveyors are rare exceptions on Japan’s sake scene well worth a look for visiting enthusiasts.

But, for those outside of Japan, there’s good news: if homebrewing is legal where you live, no one’s stopping you from trying your hand at this dead simple recipe at home!

Comments