What is terroir?

For most, French wine is the first thing that comes to mind at the mention of terroir, that ethereal characteristic in wine derived from the very environment in which its source grapes thrived. But terroir can actually apply to any food or drink whose source you can trace. Beef has terroir; cattle eat different foods depending on where they’re raised. Coffee has terroir; roasting, altitude, soil and climate all affect the flavor of the bean. So, does sake have terroir, too?

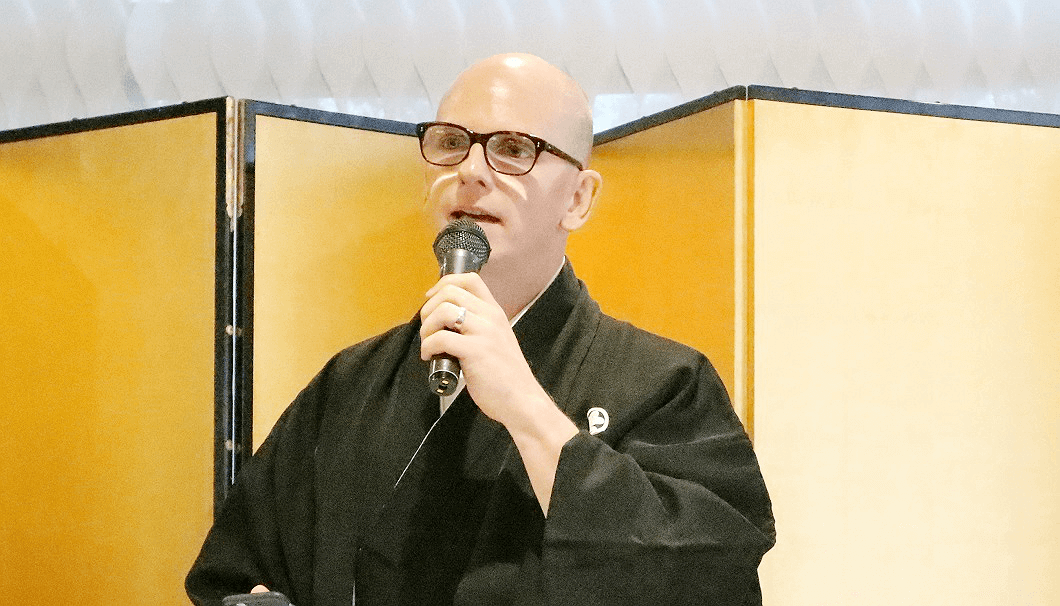

Michael Tremblay, Head National Sake Sommelier for Ki Modern Japanese + Bar in Toronto and, as of this year, an official “Sake Samurai,” presented a seminar on “The Terroir of Sake” at the 2018 Kampai Toronto event.

He says the answer to this question is, “Yes.” And, “No.”

Caption: Michael Tremblay at the Sake Samurai 2018 designation ceremony

Caption: Michael Tremblay at the Sake Samurai 2018 designation ceremony

Local geography, the ingredients (water, rice, koji and yeast), and the personality and skills of the brewmaster, or toji, can all play a role in shaping the palate and thus, in theory, the terroir, of a particular sake. But Yamada Nishiki rice, for example, produces excellent sake no matter where it’s grown. And unlike the grapes used in wine-making, rice is not damaged by transportation over long distances. This is why breweries have traditionally been more concerned with the quality of the rice over its exact provenance.

In recent years, however, some toji are starting to pay more attention to the concept of terroir as it relates to the source of the rice. Some prefectures have even tried to define their own regionality system despite Japan’s existing nationwide Geographical Indication system. Yamagata was the first prefecture to be designated under this system back in December 2016, and it appears that Hyogo may be next in line. Moving away from generic, mass-produced sake, prefectures are starting to think about how to protect their local brews’ unique identities, which would in turn give those in the sake world more concrete regional specifications to refer to when describing a sake’s terroir.

Rice

Not all grapevines grow at the same speed or in the same climate. This is why there are so many different types of wine. Likewise, many rice varietals, suited to specific climates and purposes, are grown in Japan.

Japan is not a geographically large country, but from north to south it covers over 20 degrees of latitude. Sapporo’s latitude is close to Toronto’s, while Okinawa’s capital, Naha, lines up with Miami. Combine this with the different altitudes of the country’s mountainous terrain and you end up with a lot of different climates and, naturally, growing habitats that would potentially affect the terroir of a given bottle of sake.

The rice used in sake brewing tends to be one of three varietals. Although they are now cultivated throughout Japan, Yamada Nishiki is traditionally from Hyogo, Gohyakumangoku from Niigata, and Omachi from Okayama. This means that most toji are brewing with rice native to another part of the country.

Yamada Nishiki doesn’t really grow north of Yamagata, and even there production is low, Tremblay explained at the seminar. Altitudes above 300 meters don’t suit it either. Similarly, Hyogo’s Yamada Nishiki can’t be grown in the Japan Alps of Nagano or further north. In an attempt to find a workaround to these geographical difficulties, some northern breweries have been working with farmers to develop rice strains suited to the climate and the shorter growing periods of cooler regions.

Following years of crossbreeding to develop a new sake rice that can stand up to colder temperatures, sake made with Yuki Megami (a new junmai daiginjo rice in Yamagata) debuted in 2014. Many other regions are likewise trying to wean themselves off Yamada Nishiki and grow their own local varietals.

Most breweries use Yamada Nishiki to some extent for their higher-end products, but things get interesting when they start using locally-grown sake rice. More varieties of sake rice should pave the way for more distinctive terroir profiles in these local products.

A new generation of toji are shaking things up, maintaining the traditions of the old masters while bringing in new techniques and ideas. That often includes more emphasis on terroir. The Matsumoto Sake Brewery in Kyoto, for example, prints ID numbers on its labels that correspond to the specific field where the rice was grown. At producer of Kuheiji, Manjo Jozo, in Nagoya, they grow their own rice, with labels showing the latitude and longitude of the origin field.

Mountains

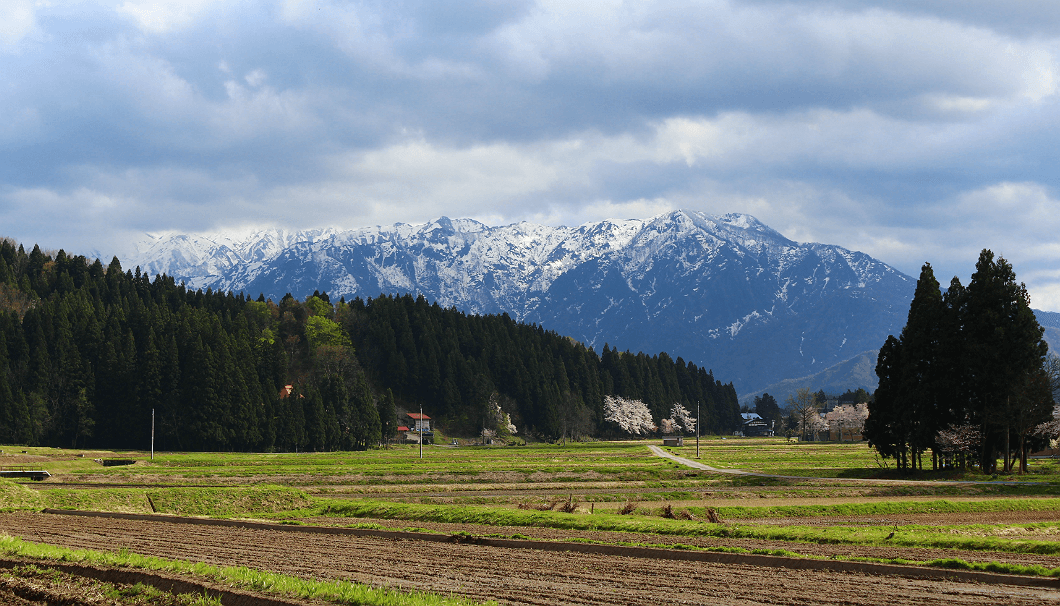

Japan is part of the Ring of Fire, a chain of tectonically-active faults running from New Zealand through Indonesia, up the east coast of Asia and down the west coast of North and South America. Japan is one of the more active parts of this chain, and the mountains created by volcanic activity make up over 75% of the country’s topography.

The prefectures are often divided by these mountains, and have developed their own identities which affect regionality, including culinary styles. Sake has evolved to go with these different cuisines, in the same way that wines in different parts of Europe characteristically pair well with the local food.

However, the main impact the mountains have on sake-making and the terroir of the finished product is in climate. In winter, cold arctic air sweeps down across Siberia. This air picks up moisture as it passes over the Sea of Japan, then rises up the country’s mountainous coast, eventually blanketing whole regions in snow. In spring, meltwater from the snow feeds rivers, lakes and aquifers that in turn provide water with unique characteristics for sake brewing. And speaking of water…

Water

With 80% of a bottle of sake composed of water and most breweries using well water, the mineral content of groundwater is an important factor in sake production. Some minerals support the actions of the yeast and koji, while others accelerate the aging process and discolor the sake. Hard water usually produces dry, full-bodied sake, and soft water often begets smoother, gentler brews.

Tremblay says both toji and sake experts have told him that most of the water in Japan is soft because of the mountains. They say that, in many places, the water flows so quickly that it doesn’t have much time to pick up minerality. Hard water, however, ensures a full fermentation, and the name “Masamune” is often given to sake brands made with water of a higher mineral content. The tradition of incorporating Masamune dates back to sake-making in the Edo period, when the elements of the fermentation process were not well understood.

Tazaemon Yamamura, the 11th-generation head of Sakuramasamune, has told Tremblay that the use of the name Masamune comes from the similarity between an alternate reading of the characters for “seishu” (a term for refined sake in Japan) and that of an alternate reading of the characters for “Masamune,” an otherwise unrelated word. Meanwhile, according to Tremblay, Tomonobu Mitobe, fifth-generation head of Mitobe Sake Brewery, explained that Masamune was the name of a famous samurai sword maker. The minerality of the water he used helped to make very sharp swords. The name “Masamune” on a sake brand in Japan, then, suggests a sake with a more angular style.Or so they say, anyway.

People

The production of sake is overseen by brewers called toji. Toji guilds developed under a system that dates back to the Edo period. Rice farmers didn’t have much to do in the winter so they would go to work at sake breweries throughout Japan when the weather turned cold, returning home with techniques they’d picked up from their offseason exploits . These traditional guild systems still exist, but new brewers are also studying at Nodai (a nickname for the Tokyo University of Agriculture, which is like the UC Davis of the sake world), keeping one foot in tradition while simultaneously departing from it in developing new techniques.

Those new techniques and approaches to sake, the local attitudes of individual sake operations, the unique characteristics of local water sources, and the ever-diversifying varieties of sake rice combine to make a compelling argument that terroir – often so inextricably connected to provenance and regionality – is an increasingly distinct and important factor in sake-making, even if the term is yet to make significant headway in the sake community’s lexicon.

Comments