KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute Makes Sake Education Accessible to the Masses

Feb. 12. 2019 writer

To survive in a harsh market, the makers of Dassai, Asahi Shuzo, needed to evolve. In doing so, they’ve found success around the world, but have they also turned their backs on tradition?

In the northwestern Spanish town of San Sebastian, known for its world-class cuisine, Mugaritz, one the area’s foremost restaurants, serves glasses of Dassai 23 to pair with their dishes. In Paris, sake fans frequent La Boutique Dassaï Joël Robuchon, established in partnership with the late Robuchon, whom many consider to be the greatest gastronomist of our generation.

La Maison du Sake is another place to find Dassai

La Maison du Sake is another place to find Dassai

Meanwhile, over in the US, the Dassai logo often adorns ceremonial sake barrels smashed in celebration of Japanese businesses’ western openings. And all around the world, anime fans watch as Evangelion‘s Misato Katsuragi slams bottle after bottle of Dassai.

Dassai’s western market domination might make it seem like it’s the only sake that matters, but it’s in fact just one of thousands of unique brands; It’s Asahi Shuzo’s ambitious outreach to new sake drinkers worldwide that sets Dassai apart.

And amazingly, they’ve mostly achieved this through creative ventures and partnerships over conventional advertising. Dassai’s success is a fine case study in bringing sake to western markets, but an exploration of how a traditional brewery works helps illuminate the daring genius of Dassai’s unconventional endeavors:

The art of brewing sake is said to date back millennia, and it’s been sluggish to evolve, for better or worse. Even the generally agreed-upon brewing season, for example, is largely the result of historical happenstance.

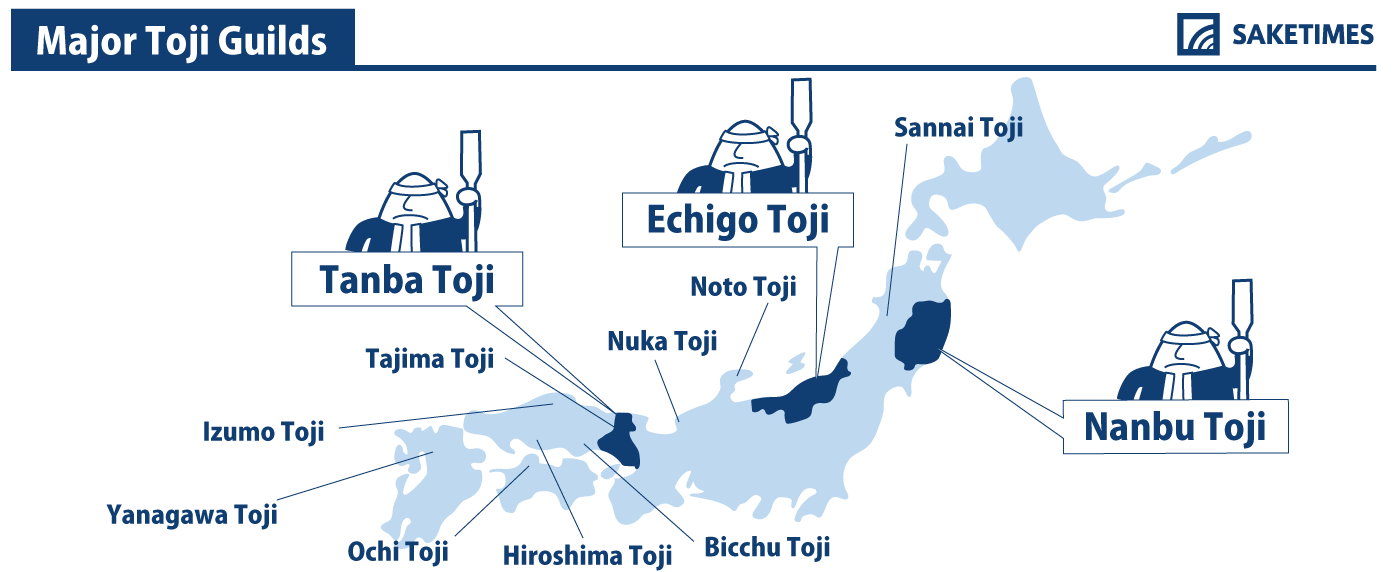

Farmhands looking for winter work outside of the growing season would congregate at breweries and go to work under the authority of a Toji. A Toji is the person who calls all the shots in the brewing process and their authority is absolute. Once the work was done, the brewery’s storehouse was full and the laborers would go back to their regular lines of work.

Toji guilds were formulated in different regions throughout Japan to seasonally hire off-season farmers and fishermen in order to brew sake in the winter. Learn more at Glossary:Toji

Toji guilds were formulated in different regions throughout Japan to seasonally hire off-season farmers and fishermen in order to brew sake in the winter. Learn more at Glossary:Toji

This was a good system for an agricultural society like old Japan, but in the modern era migrant farm hands are a dying breed to say the least. Because of this, sake breweries have had to make adjustments to maintain operations, but as much as possible try to adhere to the traditions that grew the industry in its nascency.

This could be considered both the greatest strength and greatest weakness of Japanese sake breweries, but whichever the case, the entire industry has been in steady decline. Since the mid-70s, roughly half of the breweries in Japan have folded, and those that remain struggle to adapt to a shrinking market – all except for one in particular.

In 1984, when Hiroshi Sakurai took over his father’s small brewery at Asahi Shuzo, it was already on the brink of collapse. To save the business, Sakurai needed to sell outside Asahi Shuzo’s home turf in Yamaguchi Prefecture, but since it was not historically known for sake production like, say, Niigata, Sakurai struggled to find new buyers.

It was then that Sakurai made the decision to radically alter his business strategy, choosing not to compete with other breweries for existing sake drinkers. Instead, Asahi Shuzo would target non-sake drinkers like younger people and women with the Dassai brand.

A bottle of Dassai 23 Junmai Daiginjo

A bottle of Dassai 23 Junmai Daiginjo

To accomplish this, Asahi would exploit another quirk of traditional sake brewing. Over thousands of years, brewers have determined – in very fine detail – what type of ingredients produce certain qualities in the final product, from the rice and water to the yeast and wood for the barrels.

But for new drinkers especially, it’s all Greek to them.

So, while Asahi goes to great lengths to use quality ingredients in their Dassai brand, they don’t waste their breath telling that to customers. Instead, they rely on the universal language of great taste, and let the flavors speak for themselves.

In Japan, the approach yielded positive results; Sakurai’s strategy saw Asahi’s profits steadily increase, in direct contrast to the decline other brewers were grappling with.

There were problems, though; Since Sakurai was betting all of the company’s reputation on the taste of Dassai, he had to ensure it delivered every time. That’s very difficult, since brewing sake is an organic process that relies on natural ingredients whose quality and yield are both at the mercy of nature from year to year.

In addition, the brewing work was done each winter under the exclusive supervision of the Toji. If the sake brewed in one winter was not up to Sakurai’s standards, he would be helpless to do anything about it and have to try and market it as is.

So, in 1998, Asahi did away with Toji and began brewing sake all year round.

Using their profits, Asahi Shuzo invested in methods to harvest high-quality rice in quantities large enough for year-round brewing, and started to rely on technology rather than a Toji to achieve a consistent taste. They also replaced the traditional wooden brewery with a modern 12-story building fitted with the cold, stainless steel of cutting-edge industrial equipment.

It would never be perfect, because the core ingredients were still at the mercy of the elements, but now Sakurai could at least minimize imperfections in the company’s flagship label. With this new system in place, it was time to expand even further – to global markets.

Asahi Shuzo’s Global expansion gambit proved successful, and although sake awareness is still in its infancy worldwide, the brewer has seen sales skyrocket throughout the 21st century. As mentioned earlier, they did this without any conventional advertising and also without altering their product to fit other countries’ tastes. Sakurai says this is because people generally desire authenticity in foreign foods.

But “authenticity” is not a word everyone will agree on when it comes to Dassai. Critics would argue that brewing sake is a delicate art and Asahi’s systematic approach, bordering on mass-production, reduces their sake to a facsimile of the real thing.

It’s an argument that boils down to what you think sake is and should be, and Sakurai is certainly not deaf to such criticisms. But he also points out that, had Asahi Shuzo remained a small brewery equipped with traditional wooden tanks in wooden facilities, the whole operation would have been wiped out in the heavy rains and flooding that struck western Japan in 2018.

And even back in 1984 when Sakurai began to reimagine sake production, the motivation was simple survival. The company, Sakurai contends, had to evolve or die.

He summed it up best in an earlier interview with SAKETIMES: “I always think, ‘I can’t use the same sake as yesterday,’ because our customers are always evolving… It’s a truth of humans who create and probably a primal instinct too. I will always try to improve, even if just a little. And if I ever lose that instinct, then it would be better to stop creating altogether.”

Comments