Most Americans know the story of Henry Ford and how his assembly line revolutionized manufacturing, turning the automobile from an expensive luxury item to an affordable necessity for the everyman.

Tsunekichi Okura, the 11th head of Kyoto’s famous Gekkeikan sake brewery, had a similar revolutionary impact on the sake industry. Yet, even in his native Japan, his name is not commonly known. We decided to take a deeper look at this underappreciated nihonshu pioneer.

Early Life

Okura was born into a sake-making family in 1837. His distant ancestor had founded a brewery in the Fushimi area of Kyoto, a region now renowned for its quality water, in 1637.

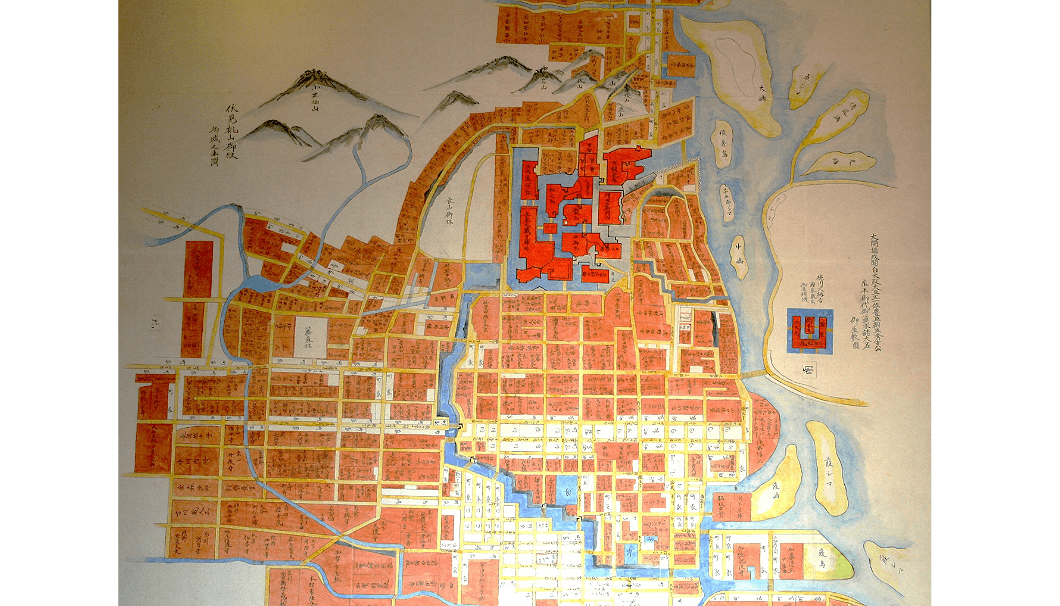

Caption: a Map of the Fushimi castle around 17th Century

Caption: a Map of the Fushimi castle around 17th Century

Okura’s family legacy was no guarantee of success, however, as the sake industry in Fushimi was in steep decline at the time. A triple threat of fires, rice shortages due to drought, and a costly bacterial contamination had driven many sake makers out of business. By 1668, the number of brewers in Fushimi had dropped from 83 in 1657 to just 2—one of which was Gekkeikan.

As the second son, Okura was never expected to take on more than a peripheral role in the family business. However, the sudden deaths of his elder brother and father in 1886 meant a 13-year-old Okura had to step up to lead the company through that challenging period despite his tender age and lack of experience.

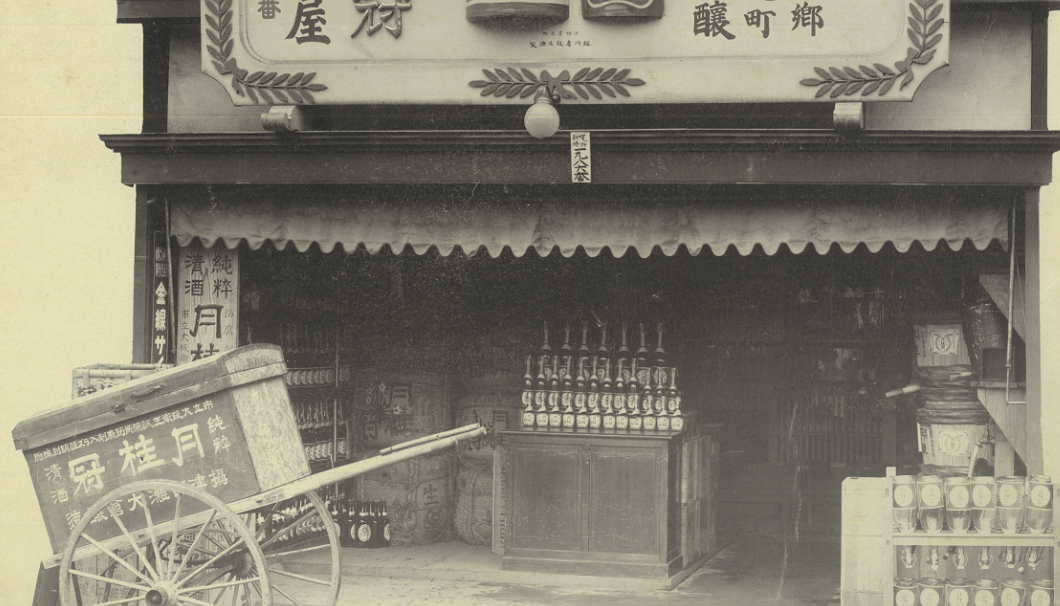

Caption: a bottle shop selling Gekkeikan sake in 19th century

Caption: a bottle shop selling Gekkeikan sake in 19th century

Encouraged by his strict mother, Ei, Okura learned the business from the ground up. Just as Henry Ford apprenticed to the machinists in Detroit rather than enrolling in school, Okura started out working in the company’s retail shop and managing the finances to get a sense of the business. He then studied under the workers in the brewery to learn each step of the sake-making process.

“During his time on-site, he experienced a lot of the issues [in the industry] first-hand. As they piled up, he felt like he needed to find solutions. Problem-solving became his approach to life,” says Shinji Tanaka, public relations officer at Gekkaikan.

“That deep understanding of the issues is the basis for his later insights, I think.”

Caption: Shinji Tanaka, public relations officer at Gekkaikan explains the story of Okura in detail.

Caption: Shinji Tanaka, public relations officer at Gekkaikan explains the story of Okura in detail.

A Scientific Mind With a Business Bent

Despite his lack of formal schooling, Okura clearly had an analytical mind, which he turned to the problems facing sake production.

Inspired by scientific knowledge flowing into Japan as a result of the Meiji Era’s new openness to the West, he experimented with methods to prevent lactic acid bacilli from spoiling sake, keeping detailed notes of his successes and failures. He often toiled late into the night after the brewing work was done and throughout the off-season as well.

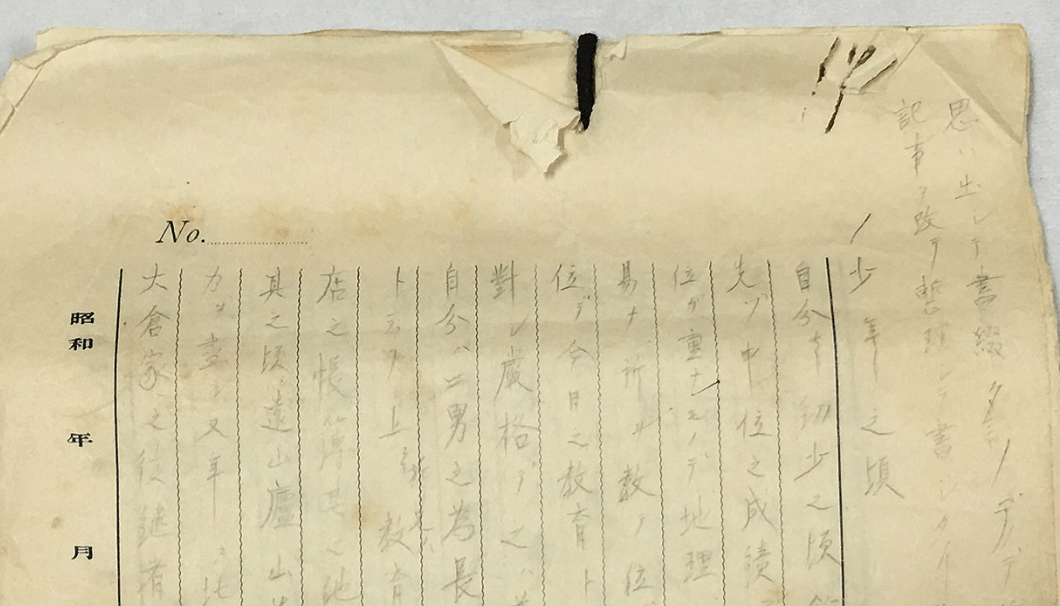

Later in life, he wrote of this dedication in his journals:

“No matter who you are, even a child, you cannot fail if you are working passionately on behalf of others. Even if it is biting through stone, you will manage it.”

Caption: a hand-written journal of Tsunekichi Okura.

Caption: a hand-written journal of Tsunekichi Okura.

He collaborated with a professor and technician from the national research institute of brewing, eventually establishing his own research laboratory on the brewery grounds and employing two technicians to apply themselves to research and development.

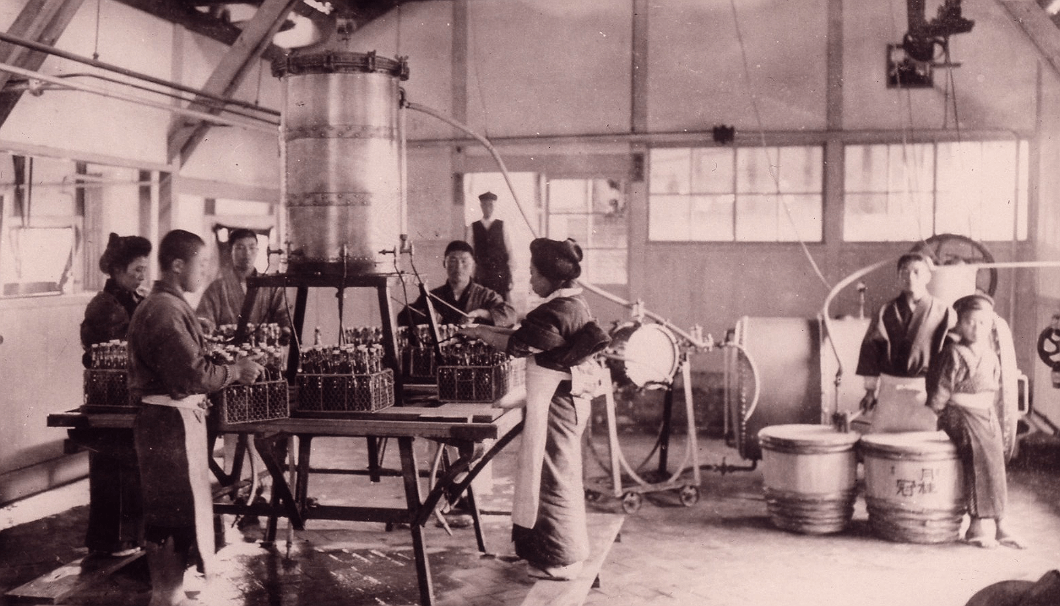

His approach was a success. Previously, sake brewing was only possible in the cold winter months, when low temps inhibited the growth of unwanted bacteria. Thanks to Okura’s research into pasteurization, Gekkaikan became the first brewery in Japan to introduce year-round sake brewing.

These methods also enabled Gekkeikan to become the first to bottle sake without preservatives. At the time, many brewers added salicylic acid to prevent spoilage, but people were concerned the additives were unhealthy. Preservative-free quickly became a catch word in the industry.

Caption: Bottling Factory in 1909

Caption: Bottling Factory in 1909

Another change brought about by the Meiji Era growth and development was a population boom. Japan went from a population of 38 million in 1885 to 53 million in 1915, many clustered in Tokyo and other major cities.

The age of the salaryman and consumerism had officially begun.

While most sake was still sold by the cask, Okura saw this changing demographic as a business opportunity. Just as Ford saw his own factory employees as an untapped market for the affordable Model-T, Okura realized the workers of Tokyo would be eager customers for bottled sake.

Caption: bottled Gekkeikan sake circa 1910. The bottle cap doubles as a cup.

Caption: bottled Gekkeikan sake circa 1910. The bottle cap doubles as a cup.

Indeed, the clean image, manageable size and consistent quality made bottled sake a hit, with Gekkeikan leading the way in commercialization. When Okura inherited his business, Gekkeikan was producing 90 kiloliters annually, by the early 20th century, it was producing 9000kL/yr.

Okura also studied and instituted Western bookkeeping—another parallel with Ford—to better understand production numbers. The approach allowed him to further manage expenses and rapidly expand the business to meet flourishing demand.

The Philanthropic Capitalist

Ford’s philosophy of welfare capitalism is nearly as well known as his technical achievements. In doubling the standard wage for factory workers, providing profit-sharing options, and instituting a 5-day workweek, Ford hoped to provide his employees with the necessities in order to good lives and enrich the community. He believed these investments in human capital would also then lead to the development of a market that inspired further growth.

Okura, too, felt a strong connection and desire to reinvest in the community that supported him in his difficult early days.

Hoping to use his influence to revitalize Fushimi’s historic sake industry, Okura was active in the Sake Brewing Association, attending monthly lectures at Kyoto Imperial University and freely sharing new information, technology and best practices.

Gekkeikan’s famed research facility was soon joined by another, run by the association itself. Fushimi garnered a reputation for cutting-edge sake production, attracting creative minds and much needed capital.

Today, about 20 breweries are active in Fushimi, and the larger Kinki region is responsible for half of Japan’s domestic sake production.

Caption: Tsunekichi Okura (right, front row), a professor of Kyoto Imperial University (2nd from left, front row), the man who taught Western bookkeeping to Okura (center, back row), a professor of the Ministry of Finance (2nd from right, front row)

Caption: Tsunekichi Okura (right, front row), a professor of Kyoto Imperial University (2nd from left, front row), the man who taught Western bookkeeping to Okura (center, back row), a professor of the Ministry of Finance (2nd from right, front row)

Fire was a common risk in Meiji-era Japan and often devastating for sake producers and sellers. Okura provided a fire engine for public use and donated land next to the head office to establish a local fire department, which is still in operation today.

Many of his other projects can still be felt in present-day Fushimi. Okura donated the funds and equipment to establish the first town hospital and remained a patron to support its continual improvement.

He supplied facilities and teaching materials for a kindergarten, provided educational scholarships for local children, and paid for a community center to be built at the local shrine, thus establishing a base of local and community-driven relationships the company continues to foster to this day.

A Living Legacy

Okura died November 17, 1950, at the age of 77. The company passed to his son and now to his grandson, but Okura’s tenacious spirit of innovation lives on at Gekkeikan. It was one of the first Japanese sake brewers to set up production facilities in North America, just ahead of the current sake boom.

As head of the engineering at Gekkeikan, Yohsuke Yamanaka oversees the vast array of modern machinery now used by the company. What makes Gekkeikan stand out, he believes, was born of Okura’s scientific approach. Any time he encounters a problem or needs inspiration, he can consult the company’s treasure trove of research notes, drawing on centuries of experience in sake production.

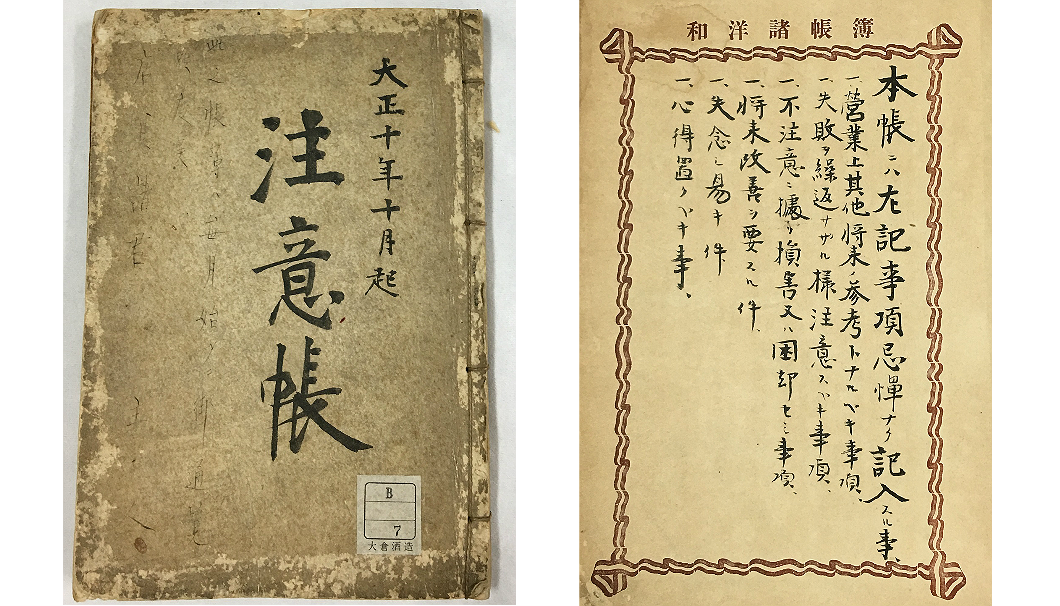

Caption: research notes by Tsunekichi Okura, dated 1921.

Caption: research notes by Tsunekichi Okura, dated 1921.

“One thing that is unique about sake making at Gekkeikan is the various kinds of data we have, going back into the distant past,” says Yamanaka.

“We can look back and see how they did things back then. Access to that amount of quality data, it just isn’t found elsewhere.”

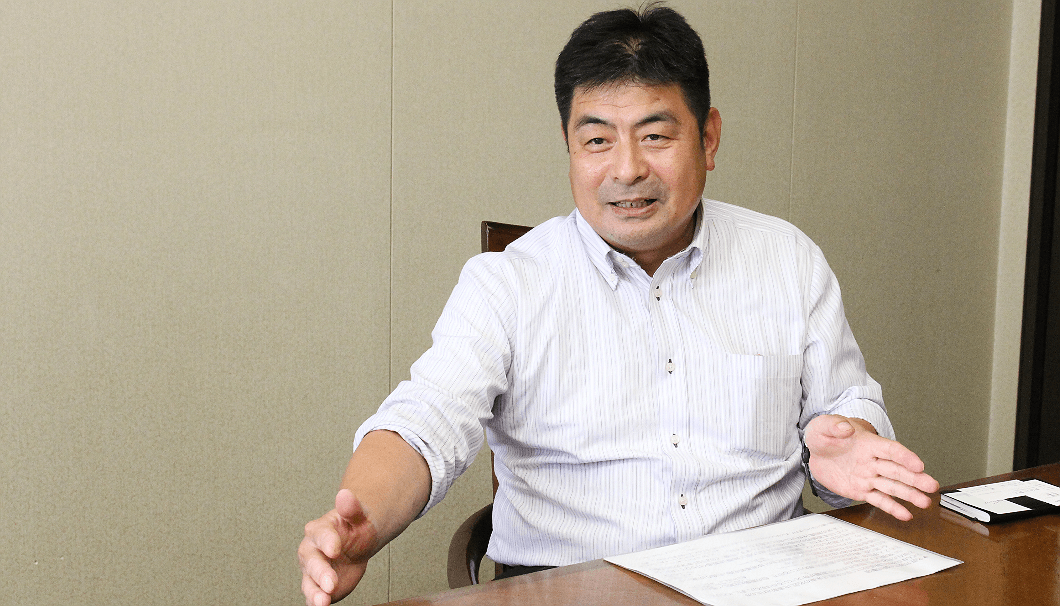

Yohsuke Yamanaka, head of the engineering at Gekkeikan.

Yohsuke Yamanaka, head of the engineering at Gekkeikan.

Tsunekichi Okura’s name may not ring many bells outside the halls of Gekkeikan, but it is hard to find a facet of life in Fushimi—and the world of sake—he hasn’t touched.

He would surely be satisfied to see his company thriving as one of the most prolific sake producers in the industry today, continuing with his philosophies, and poised to usher in the next revolution in the world of sake.

Comments