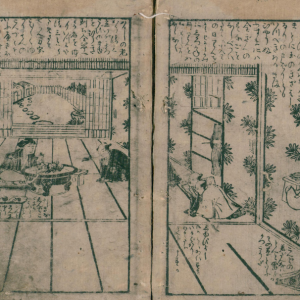

Compared to noh drama, which is slow and stately – reflective of the fact that the plays are based on ancient poems and courtly literature – kyōgen, which dates from the same period, presents the humorous struggles of daily life. Quarreling lovers, boastful liars, and crafty servants trying to fool their employers abound in these stories. Any program of noh plays has a kyōgen drama at a midway point to serve as comic relief. Once the performers of the more elegant noh have left the stage, the actors of kyōgen, literally “mad words,” come crashing in, bringing hilarity to balance noh’s weighty themes of longing and loss. If noh teaches us to explore the depths of mystery and beauty, kyōgen illustrates how ordinary people can do funny things, with sake often being the root cause behind the humorous happenings.

Kyōgen and noh developed in the late fourteenth century from the medieval performing art sarugaku, or “monkey music.” Noh performers, exemplified by the playwright Zeami (c. 1363-1443), sought to elevate their art from the skits and antics of sarugaku. Kyōgen actors borrowed many of noh’s aesthetic principles such as its minimalistic staging, but kept the lowbrow humor of sarugaku. Noh actors mesmerize the audience with their formal movements accompanied by chanted poetic verses from a chorus. Kyōgen strips down these aesthetics to usually just two or three actors who speak colloquially and rarely wear masks, which are a trademark of noh.

Noh’s Drunken Elf

The different theatrical worldviews of these forms of theater can be seen in how they represent drinking. In the noh play Shōjō, a seller of spirits wonders why his favorite customer can consume so much alcohol and not turn red in the face. The customer reveals that the brew does indeed affect him, and declares himself to be Shōjō, the “Drunken Elf.” Appearing in a red-faced mask, he expresses his intoxicated joy in dance, giving his supplier a magical container that will always pour out fresh brew. The merchant rejoices, but then wakes to discover it was all a dream. Noh frequently breaches the line between reality and illusions, inviting audiences to explore the world of dreams, which some viewers do too literally, falling asleep due to the slow pace of the plays.

Kyōgen’s “Auntie’s Sake”

Compare noh’s Shōjō to the kyōgen play “Auntie’s Sake” (Oba ga sake) that features another alcohol merchant, this time a woman who owns a sake brewery. Her nephew pesters her to sample her wares, but she worries that he will consume all her profits. After exhausting his best arguments about why he should be given a drink, the nephew leaves, hinting about rumors of a demon haunting the area. The nephew dons a demon mask, returns to his aunt’s, and scares her away when she opens the door. With his aunt gone, he can have his fill of sake, but he first must slide his mask to the side of his face to drink. The kyōgen actor uses a fan to mimic a large cup of sake the nephew drains again and again, and it is not long before he passes out.

Meanwhile, the aunt summons her courage to return to discover that the sleeping demon is her obnoxious nephew. She takes the mask and shakes him awake. He tries to act like a frightening monster again, but his aunt yells at him, holding the mask in her hands. The nephew apologizes and stumbles away with his aunt calling threats behind him in a chase scene that is a typical ending for kyōgen plays. Far from the elegant dreams of noh, kyōgen presents the medieval Japanese equivalent of a vaudeville act or a television skit.

Tie That Sake Lover to a Pole!

In one of the most iconic kyōgen plays, a wealthy man believes he has a surefire method to prevent his servants from drinking his sake. Before leaving home, he ties up his servants, one with his hands behind his back and the other with his arms to a pole, hence the name of the play “Tied to a Pole” (Bōshibari). With the sake containers in sight, the two servants at first feel defeated. But the one with his arms tied to the pole realizes he can still move his hands, so he opens the lid of a sake jar and dips a cup inside allowing his comrade to sip. Watching his friend drink his fill, the pole-tied servant tries to swallow some sake by himself, but his hands are too far away from his mouth and he only splashes his face. Fortunately, his co-conspirator holds the cup for him and the two help each other to drink until they are satisfied. Now drunk, they sing and dance all while still tied up, laughing until their boss comes home to discover that his best plans to preserve his prized sake are ruined. Furious, he chases the laughing servants off stage.

On a typical day at the noh theater, audiences can watch both noh and kyōgen plays, the latter providing comic relief from the sweet sadness of noh. Both theatrical arts made important contributions to sake culture as witnessed by the many artistic representations of noh’s drunken elf, Shōjō. But kyōgen’s mundane world is more approachable, since its humor remains timeless. Audiences today, just like those of 600 years ago, know the trouble folks can get into when they drink too much of a good thing.

Comments