Kibyōshi are Japan’s first comic books. Dating from 1775 to the first decades of the nineteenth century and named for their yellow covers, these ten-page booklets interspersed large images with text to tell satirical stories. Of the 2,000 kibyōshi known to exist, many mention sake in passing and some make sake their central focus. Collectively, they provide important records about the sake world in the latter part of the early modern period (1600-1868).

Dreaming to be a Wealthy Sake Merchant

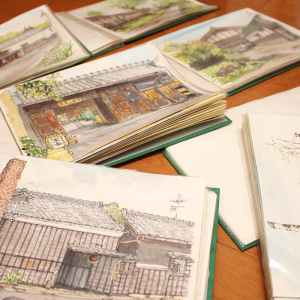

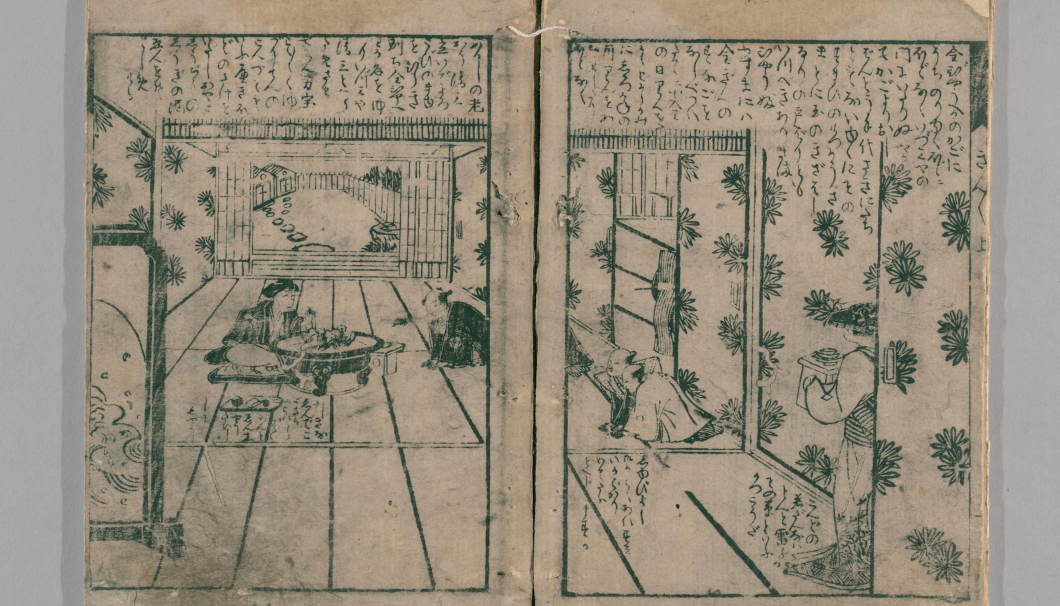

Sake features in what is considered the very first kibyōshi, Master Flashgold’s Splendiferous Dream (Kinkin sensei no eiga yume) by Koikawa Harumachi (1744-1789), printed in 1775. Adapting a noh play in which a man dreams he has become the emperor of China, Koikawa’s dreamer falls asleep in a sweetshop in Edo (now Tokyo) waking to learn that he is now the heir of a wealthy sake brewer. The size of the brewer’s mansion, shown in the image above, represents enormous wealth with large rooms that lead to a garden and storehouses in the distant background. Master Flashgold (center) bows to the sake brewer seated at a large brazier on the left. Male servants wait for orders while a maid brings cups for the brewer’s most divine tasting sake to be used in a ceremony that will formalize Flashgold’s inheritance.

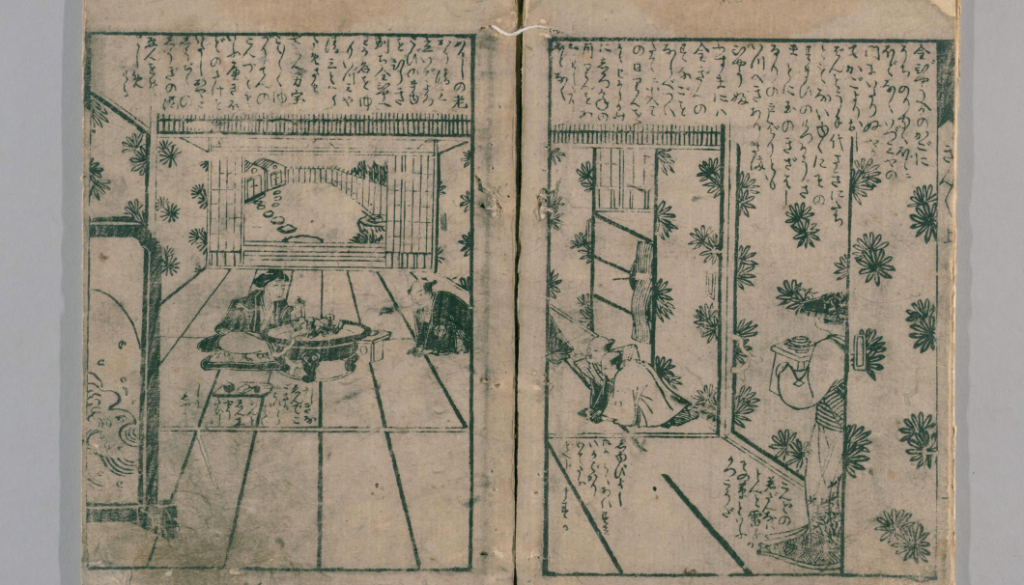

Flush with cash and eager to spend it, Master Flashgold celebrates in grand style with evenings of drinking and female companionship, as depicted in the scene above. Seated on the right, Flashgold holds a large sake cup in his hand ready for the attendant to fill it from the warming kettle (chōshi). Close by are delicacies on short tables that include a whole fish, as entertainers perform for Flashgold’s pleasure. But all pleasant dreams must come to an end, and Flashgold’s wealth disappears in a flash when he wakes up back in the sweetshop.

Readers can find a complete translation of this story by James Araki in Early Modern Japanese Literature, An Anthology, 1600-1900 (Columbia University Press, 2004).

Sake Becomes the Comic Book Hero

Cultural historian Hata Yuki has extensively researched kibyōshi that mention sake, and she has identified four examples where sake not only features but also takes life as a character.

The most famous of these stories is A Fondness for Sake: The Whirling Chronicle of Great Peace (Sake kuse: Kudamaki Taiheiki) published in 1788, written by Shicchin Manpō and illustrated by Kitao Masayoshi. Stories of inanimate objects coming alive and having human adventures was a popular genre of Edo period visual and print culture including woodblock prints, as described in a previous article.

The hero of A Fondness for Sake is not just any sake-human but the brand Kenbishi, one of the oldest and most famous of the early modern age. On the night they took revenge for their lord’s death in 1702, the famous forty-seven ronin were said to have toasted each other with Kenbishi. And, Kenbishi was the favorite brand of one of Japan’s greatest shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751).

Consumers in Edo preferred Kenbishi and other brands from the modern Hyōgo and Osaka areas over their local brews, so it is fitting that Kenbishi’s antagonist in the story is a local sake made worse by being served at room temperature. In the early modern period, consumers preferred warmed sake (atsukan) from the ninth lunar month to the start of the third lunar month (roughly October through early April); and according to the era’s dietary experts, warm sake was supposed to be healthier. Kenbishi in the tale is hot in terms of his popularity, good looks, and serving temperature in contrast to his enemy, the local sake of Edo, tepid in temperature and character.

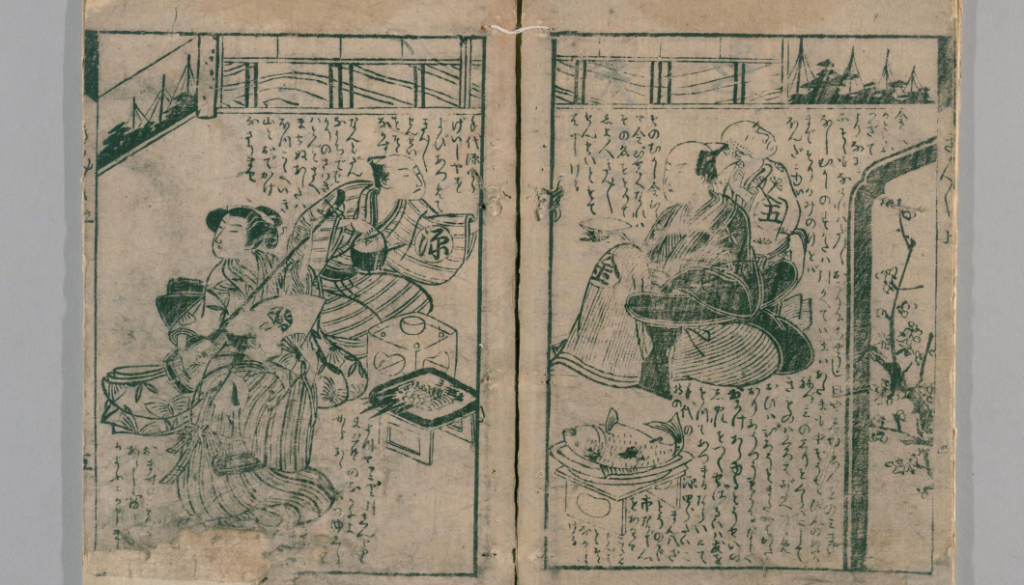

Armored in a sake barrel like the type visible at the gateways of shrines today in Japan, the heroic Kenbishi (right) holds a large sake cup in one hand while threatening to draw his sword on the local sake of Edo who cowers in the lower left of the image above. Besides their sake barrel breastplates, the shoulder and shin guards of the warriors’ armor are account books used to keep track of sake sales. The artist has thus repurposed the familiar material culture of sake into weapons of war and adornment.

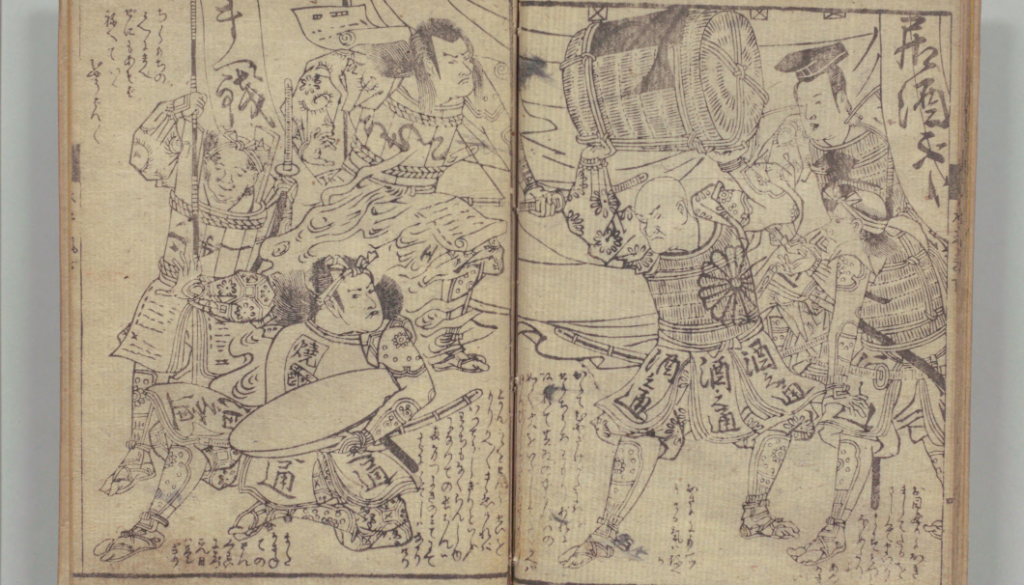

Kenbishi’s battle with the sake of Edo comes to a conclusion with the intervention of a character Professor Hata identifies as Nigorizake holding a sake barrel over his head in the scene above. That Nigorizake claims center stage may reflect the economic conditions of the time. Famine hit Japan the year before A Fondness for Sake was published, which raised the price of rice and sake, so many drinkers in Edo shifted to less expensive nigorizake. According to Hata, despite revealing a lot about sake culture, most yellow books do not mention sake brand names, but Fondness for Sake’s promotion of Kenbishi verges on being an advertisement.

Japan’s first comic books, kibyōshi, were meant for an adult audience, so it is no wonder that they would feature an adult beverage, sake. But they also cast sake in imaginative roles as heroes and even villains, giving early modern readers much to imagine as they read and sipped.

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments