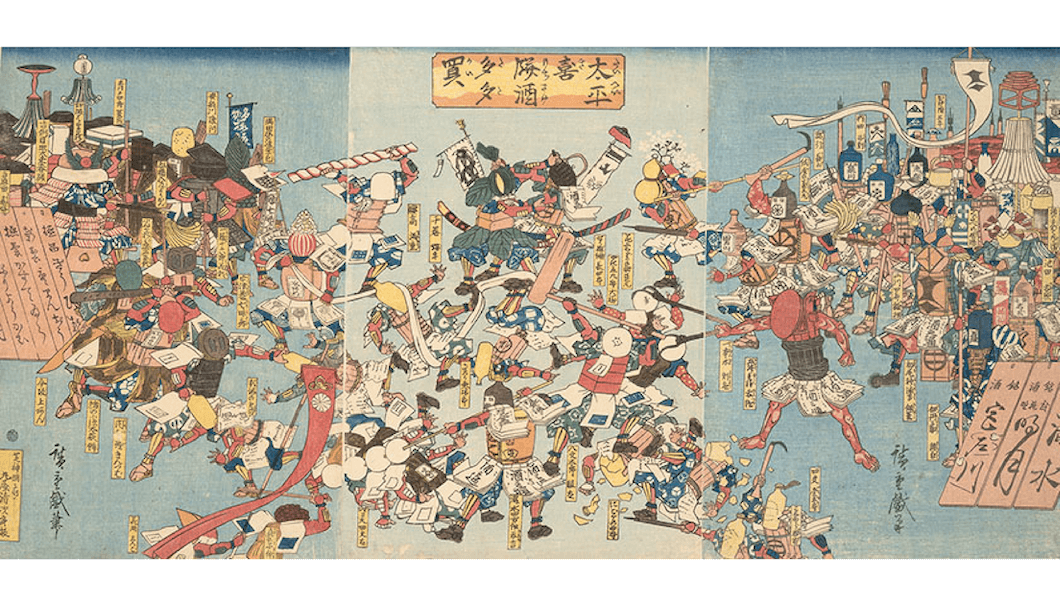

Sake cups and containers come to life, charging to meet their foes while an opposing army of sweets takes human form. Armed with candy weapons and the tools of their respective trades, the two sides clash with reinforcements in tow.

The scene sounds like the world of Japanese animation. But this vision of culinary mayhem depicted in Utagawa Hiroshige’s triptych, “Peace, Joy, and the Price War Between Sake and Sweets,” dates from more than a century ago, demonstrating that the idea of drinks and food coming to life has long fascinated audiences of Japanese popular culture. But why would sake fight sweets and why would an artist famous for landscapes create such a scene?

Food and Sake Battles

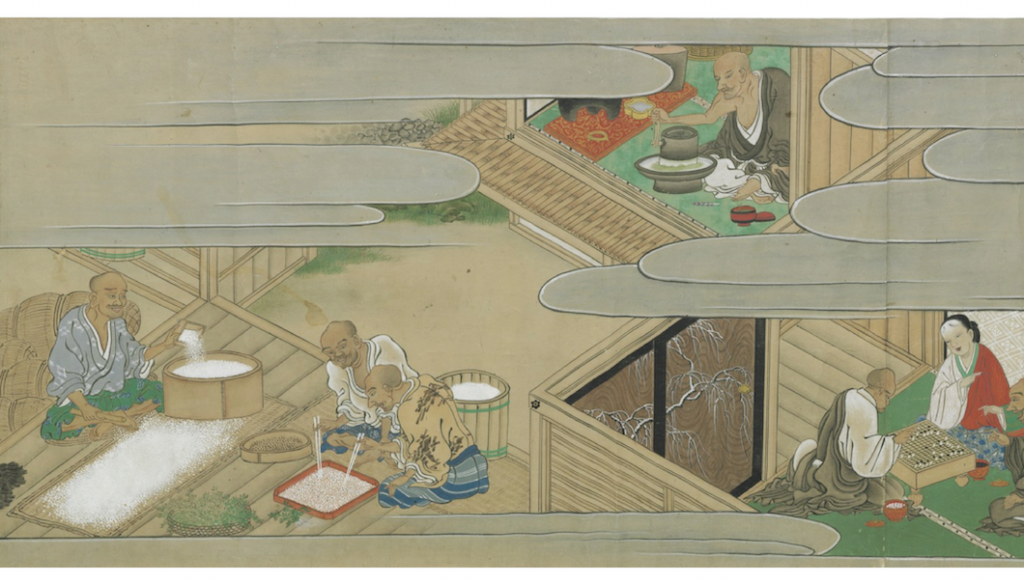

While some artists might think that food and drink are too pedestrian to depict in art, others recognize their importance to daily life and give them a starring role. In Japan one of the most famous representations of sake and food is the “Illustrated Scroll of the Sake and Rice Debate” (Shuhanron emaki), a picture scroll from the 16th century that was copied many times in the early modern period (1600-1868). In the text, two protagonists sermonize on the merits of their favorite delicacies, and the artist depicts the preparations for banquets as well as the after effects of drinking too much, with guests staggering and vomiting in one scene.

In the aforementioned picture scroll humans laud their favorite consumables, but in other texts the foods and drinks themselves come to life to explain what makes them great. Stories about foods battling beverages have deep historical roots in East Asia with the earliest examples dating from the Tang dynasty (618-907) in China.

In her 2021 doctoral dissertation at Cambridge University, Elena Follador documents dozens of examples from Japanese literature and the visual arts that feature edible characters. The humor in such works was the fact that not only was it absurd to think that foods and beverages could actually talk, but also that they would even need to argue when they existed harmoniously in the same meals. Literate audiences would further enjoy the references to famous works of literature and the witty word play as the food and drink heroes introduced themselves and advanced their positions, features that Hiroshige’s print also demonstrates.

The Artist: Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) is one of the most famous creators of landscapes of the “floating world,” or ukiyoe. Hiroshige’s “Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido” documents beautiful sites along the road that linked Kyoto with Edo (now Tokyo). In other print series he captured views of Mount Fuji and the famous places of Edo. Hiroshige’s landscapes always show the human experience in nature whether he is sketching a few distant travelers on a coastal trail or showing moments when people pause to admire a view. His 1834 print “Cooling off in the Evening at Shijogawara” depicts a nighttime sake party in Kyoto. Note the small choko sake cups scattered around the revelers, some of whom are dancing, clear signs that their fun is well under way.

Hiroshige’s “Peace, Joy, and the Price War Between Sake and Sweets” (Taiheiki mochi sake tatakai), produced between 1843-46, nods to one of Japan’s greatest war tales in its title, The Chronicle of Great Peace (Taiheiki), which describes the wars between two imperial factions in the 14th century.

But how that epic translates into the sake and sweet characters battling in Hiroshige’s triptych is an open question. One clue is that Hiroshige wrote the word Taiheiki with Japanese characters that could be read phonetically to suggest the famous war tale but could also be interpreted literally as “price war” or as “buy lots and lots.” Thus, these battling luxury goods are not as much struggling against each other as they are fighting for the attention of consumers. Hiroshige’s print was priced to be affordable for people who may not be able to purchase the best sake and sweets every day, so would have found his artwork appealing as a visual replacement. In other words, by featuring many examples of noted confectionery and famous brands of sake on the same print, Hiroshige created an early example of “food porn.”

The Battle of the Sake and Rice Cakes, ca. 1845

Color woodcut

Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Bequest

of John H. Van Vleck, 1980.2204a-c

Through heraldry and labels, Hiroshige reveals the identity of his cast of warriors. On the right side among the sake troops flies a banner for the brand Kenbishi. The Kenbishi trademark looks like an exclamation point but actually depicts a sword (ken) over a water chestnut (hishi). Other famous brands in the lineup include Otokoyama and Kamiya from Itami in modern Hyogo Prefecture. Edo’s connoisseurs thought that the sake from Itami far exceeded their local brews, so they paid a premium for those brands. Among the sake warriors is Itaminosuke Morohaku, whose impressive name indicates a sake made entirely with white rice (morohaku) from Itami. A presumably less expensive nigorizake is personified as Nigori no Shiro, whose given name Shiro suggests the white (shiroi) color of unfiltered sake. The print also pays tribute to sake consumed at important seasonal rituals such as the first visit to a shrine on New Year’s Day.

Most of the sweet forces are variations of rice cakes (mochi). Prominent among the confectionery is a samurai wielding a long poll that looks like a candy cane. His head is a giant steamed bun. He is armored around the torso with a box for steaming sweets with protective flaps at the waist made from wrapping paper. His allies include candies and a Castilian Cake (kasutera), a baked sweet that shows the legacy of Iberian influence on the Japanese confectionary repertoire.

Every time we look at Hiroshige’s print, we might discover something new, a fact that audiences of sweet and sake lovers would have likewise appreciated more than a century ago.

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments