Sake enjoys a global fanbase for its fruity sweetness and its ability to complement a range of foods . In Japan, though, it battles with shochu – another major alcoholic drink not as well-known overseas – for boozy beverage dominance.

While fairly equal in standing, these beverages are very different in terms of production process and flavor, not to mention alcohol content. To truly appreciate sake, it’s good to have a working knowledge of Japan’s other “native” beverage, and how the two differ and relate. Here’s a field guide to break it all down:

Production

In a process that some believe dates back 3,000 years, sake is brewed by converting the starch of rice into sugar and then to alcohol through the power of a specific yeast.

Shochu, on the other hand, is a distilled liquor dating from the 16th century. Distillation is the process of separating a combination of liquids with different boiling points – in this case water and alcohol. By removing some water content from an alcoholic mixture, distillers are left with a considerably stronger drink.

By comparison, then, the naturally-fermented mixture of alcohol and water that makes up sake is usually about 15 or 16% ABV, while shochu can hover around 25%. This difference, unsurprisingly, comes through in the flavors of the two drinks; sake’s being mellow and tangy, and shochu’s being dry and featuring a strong alcoholic bite.

But those are simplistic explanations of two classes of drinks that boast a wide range of flavors, so it’s also important to look at what goes into making each one.

Ingredients

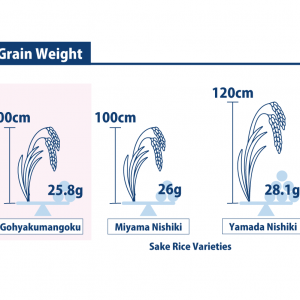

The key ingredient of sake is rice. Japan’s liquor laws, in fact, only allow for rice, koji, and water in the ingredient list for real-deal sake. That being said a number of other factors such as the degree to which the rice is polished, whether or not the sake is treated with a legally permitted addition of small dose of distilled spirit, or the variety of yeast used for fermentation can all significantly impact the product’s flavor.

Rice being prepared for brewing

Rice being prepared for brewing

On the other hand, any fan of shochu will tell you that its real charm lies in the amazingly diverse selection of raw ingredients that can go into making it. The two most popular ingredients are imo (sweet potato) and mugi (wheat). Imo-shochu has an underlying sweetness to it that appeals to those who like a stiff drink but aren’t fond of the burn of harder stuff. But for those who prefer the crisp kick of mugi-shochu, imo-shochu can come across a little murky-tasting.

Those two flavors are usually what’s offered at restaurants and readily sold in stores. But a variety of creative ingredients can yield shochu; including corn, chestnut, and raw sugar, which are all added in the second stage of fermentation.

Different ingredients yield vastly different flavors, so sticking with shochu can be a rewarding experience even if the common imo and mugi varieties don’t suit your tastes.

Rice Shochu

Rice shochu (kome-shochu) is another not-uncommon variety that is, in essence, distilled sake with distinctive shochu characteristics.

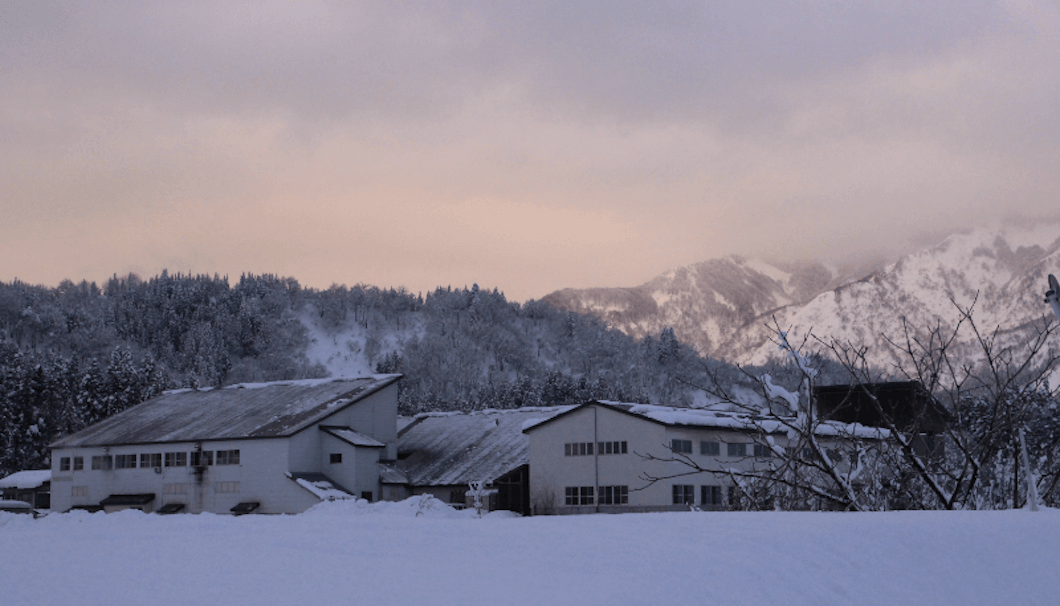

Hakkaisan Brewery, for one, makers of the famous Hakkaisan brand of sake, also sell Yoroshiku Senman Aru Beshi kome-shochu. Using the same tried and true techniques Hakkaisan puts into making sake, they additionally incorporate sake lees during fermentation to achieve a sake-like aroma that endures the distillation process and lingers in the harder shochu for a more pleasant tail.

Other notable sake breweries that also dabble in shochu include Tenzan Shuzo, makers of the exquisite Shichida Junmai Ginjo Omachi 50 sake, as well as its counterpart, Shichida Junmai Shochu. Going back 400 years, and almost as old as shochu itself, the historic sake brewery Takagi Shuzo also produces Juyondai Hizo Junmai Shochu, based on its famous Juyondai sake brand.

Drinking Shochu

Depending on the type, sake can be enjoyed at an impressively wide range of temperatures from near-freezing (5℃/41℉) to near-scalding (about 50℃/122℉). But, it can also easily be enjoyed straight from the bottle at room temperature.

The cups from which sake is drunk are also very important, but shochu is generally drunk from regular glasses.

The cups from which sake is drunk are also very important, but shochu is generally drunk from regular glasses.

Shochu too can be consumed at very high temperatures, but it’s typically not the recommended format. Instead, like most strong spirits, shochu is usually served on the rocks or cut with hot or cold water, and even tea.

How to Tell the Bottles Apart

Even for those with a working knowledge of the Japanese language, shopping around for sake or shochu can be a little tricky. Breweries and distilleries like to use complex kanji characters in their names and the bottles can look very similar to one another.

A bottle of Ginka Torikai Shochu (left) and Tadatada Junmai Sake (right)

A bottle of Ginka Torikai Shochu (left) and Tadatada Junmai Sake (right)

There are some differences to help identify shochu brands; for one, shochu often comes in short, stout bottles compared to sake’s (usually) tall and slender vessels. These aren’t iron-clad rules, though, so taking a moment to double check the label is advised.

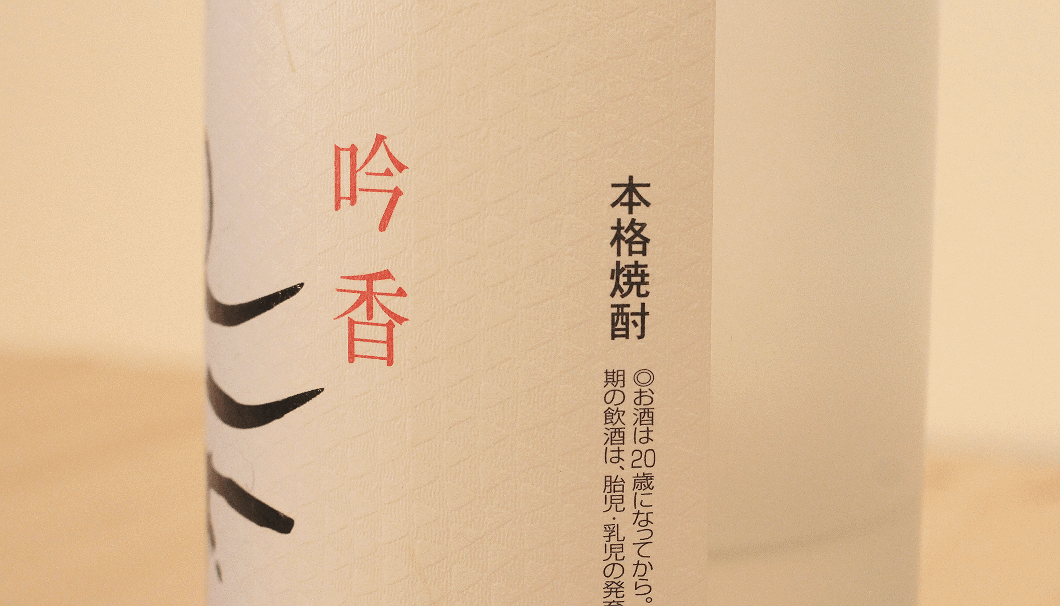

To find out what’s inside of a particular bottle, just check the corners of the labels. There will often be a series of kanji characters, with one very important symbol in particular clearly identifying a bottle of shochu.

The last kanji in each name is similar and contains the symbol (酉), a pictograph of an ancient drinking vessel. For sake the bottle is on the right side of the kanji (酒), but for shochu, it’s on the left side and features additional kanji radicals on the right (酎).

If the bottle’s on the right, that’s sake alright!

If the bottle’s on the other side, that’s shochu you just eyed!

Now that you know how to distinguish sake and shochu, you can use this knowledge to fully explore the rich world of Japanese alcohol that these two types of drinks represent. There’s bound to be something for everyone’s taste out there and finding your best match is sure to be a fun series of experiments!

Comments