Sake is often described most simply as “Japanese rice wine” (nevermind that it has more in common with beer), so we can deduce from the name that it’s made with rice. And naturally, as with grapes, different varieties of rice impart different characteristics in sake. While a sake’s flavor is impacted by specific brewing style, rice milling rate, or the type of yeast used – all of which are ultimately decided by the toji brewmaster, rice variety certainly effects the final product.

A Big Heart

Although historically, people made sake with commonly available table rice, over time different strains have been bred as sakamai (sake rice), specifically for use in sake brewing. There are significant differences between the rice served with a meal and varieties used to make sake. And although of all the rice grown in Japan only 4% is shuzokoteki-mai (rice suitable for making sake), there are about 100 represented there.

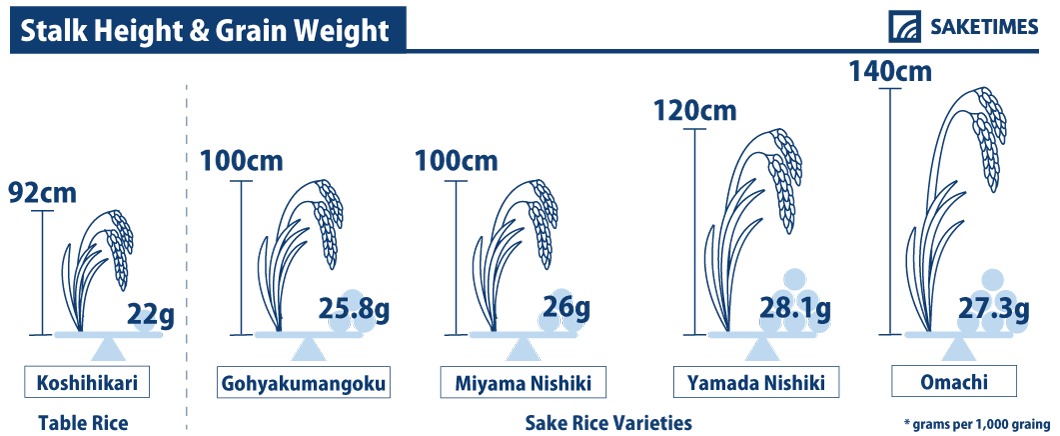

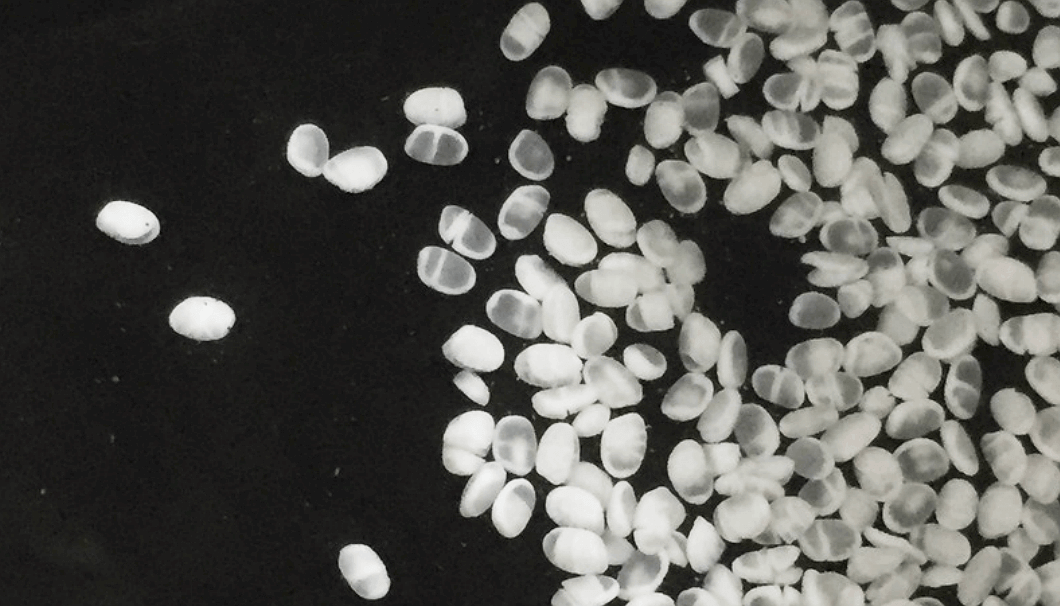

The differences start with the rice plants, which tend to be taller, with longer ears. The grains themselves are bigger, with a much larger starchy white core or shinpaku (literally, “white heart”). These larger grains are less likely to crack and jeopardize the starchy center, an essential element the yeast feeds on, during the polishing process, making it possible to remove more of the proteins, lipids and fats from around the shinpaku. The shinpaku also dissolves more easily in the moromi (mash).

Holding it Together

The seimai buai (polishing ratio) is an important factor in sake brewing; a high polishing ratio (more of the grain remains after polishing) yields complex, rich sake that have a stronger rice flavor, often being a suitable candidate for serving warm. Conversely, a low polishing ratio produces lighter sake with a cleaner taste best enjoyed cold.

In table rice, the proteins and other nutrients are spread more evenly through the grain. In sake rice, however, these same nutrients can mar the flavors and aromas of the sake as they cause too much fermentation of the yeast. That’s why sakamai polishing ratios tend to start at 70%, which is where tokutei meishoshu, or “special designation sake,” honjozo starts. At 60%, we reach ginjo level, and rice polished to 50% or less is used in daiginjo.

Polishing beyond 70% is expensive – it takes more time, with the grains becoming more fragile as they get smaller. The rice must also be allowed to cool for at least two weeks after polishing, to prevent the damage that can be caused by immediately immersing it in water.

In the Fields

Now that we understand how table rice and sake rice are different, and how polishing affects the flavor, how about the actual varieties of sake rice?

Japan is obviously a small country, but it extends a long way from north to south and much of it is mountainous. And it’s so narrow that the furthest point from the ocean in Japan (the city of Saku, Nagano) is only about 115 km from coastline. This range of latitudes and altitudes, combined with the close proximity of the surrounding seas, makes for drastically varied climates in which to grow rice.

An important distinction in sake rice varieties is between okute (planted and harvested late) and wase (planted and harvested early). Okute rice existed prior to WWII, and is characterized by larger, juicier grains and produces full-bodied sake. Wase, on the other hand, was developed around 1955. It’s sturdier against Japan’s colder climate areas, and the smaller and harder grains don’t break up as easily in the moromi. Sake made with wase rice tends to feature a lighter flavor.

Sake breweries tend to contract with farmers to produce the sake rice they need. The farmers are guaranteed an income, enabling them to focus on quality, rather than quantity. Quality is so important that, it is sometimes said, if the rice is damaged just before the harvest, farmers will refuse to sell it to breweries as a point of pride.

Blending of rice variety is less common among premium sake. A common practice in other grades, some brewers may use Yamada Nishiki for the koji – the ingredient that most strongly influences the flavor of the sake – and a cheaper sake rice for the rest.

Naming Names

While the name of the sake rice is not always listed on the bottle, here are some to watch out for if you want to learn more about how the rice affects the flavor of the sake. The first four are the most popular, but Omachi is unique in being a pure strain, while Koshi Tanrei is a new variety developed in Niigata.

Yamada Nishiki is sometimes called the “King” of sake rice. Grown in Hyogo, as well as Fukuoka, Tokushima and Okayama, this okute rice is often used to make the more delicate styles of premium sake, especially daiginjo. Yamada Nishiki absorbs water and dissolves relatively easily, and its soft grains require great care in polishing.

Gohyakumangoku is the second-most widely used sake rice in Japan. This wase rice is grown along the northwestern coast, especially around Niigata, where it was discovered in 1938. Its large inner core is almost pure starch, and it yields light-bodied sake with a fresh, clean taste, but the giant core prevents a high level of polishing.

Miyama Nishiki is also a wase rice. It grows well in cold weather and produces rich sake with strong rice flavors. It’s grown in Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Miyagi, Fukushima and Nagano, often at higher altitudes.

Omachi, grown in Okayama, is one of the few strains of sake rice that is still “pure.” While not a result of cross-breeding itself, this okute rice has been used for that purpose to such an extent that it’s a genetic parent of 60% of all sake rice. It was popular as a table rice in the Meiji Era, but when production became more industrialized Omachi was found to be too difficult to harvest by machine. By the 1920s it had dropped off the scene completely, not returning until the 1980s. Sake made with Omachi rice have an earthy taste that reveals a variety of subtle flavors within.

Koshi Tanrei is the “child” of Yamada Nishiki and Gohyakumangoku, and a perfect example of terroir in sake brewing. With Niigata’s cool climate, Yamada Nishiki had to be imported from other prefectures. Niigata’s brewers wanted a local sakamai that would offer a similar flavor profile or even something richer. And although Gohyakumangoku is a Niigata sakamai, its small grains make it is more likely to crack during the polishing process. Finally released in 2004, Koshi Tanrei has inherited all of its parents’ strongest features and none of the negatives. When the first Koshi Tanrei sake hit the market in 2007, made by local brewers, it won plenty of awards at the Zenkoku Shinshu Kanpyokai (National New Sake Championships).

Learn more about Yamada Nishiki and Sakamai

Learn more about Yamada Nishiki and Sakamai

There are many other varieties of sake rice to explore. While rice may not have quite the impact on sake as grapes do on wine, it’s still a key ingredient in sake production that can influence flavor and even mouthfeel in subtle ways, and amateur sake sommeliers owe it to themselves to taste the difference for themselves!

Comments