Tsunekichi Okura: The Henry Ford of Japanese sake

Aug. 23. 2018 writer

"We’ve reached an age in which producing great sake isn’t necessarily enough to translate into great sales."

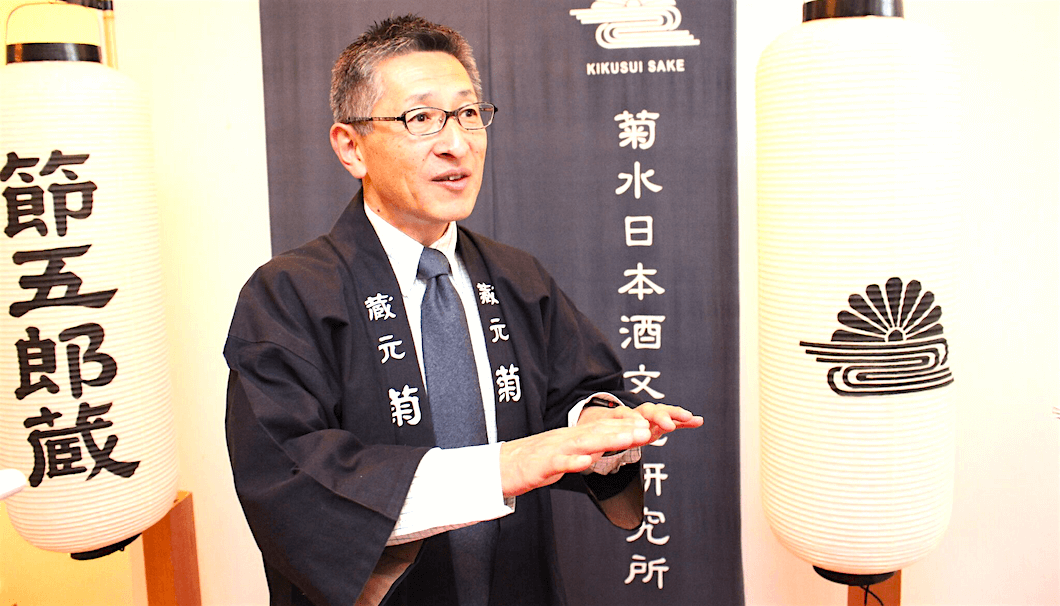

Incongruous with the seemingly pessimistic statement, this is how an ebullient and grinning Daisuke Takasawa welcomes throngs to the grand opening of KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute, a full-fledged sake education and culture center and something of a pet project for the 18-year KIKUSUI president.

“We’ve always been good at crafting, but up to now we haven’t done a sufficient job at fully communicating what that means,’” Takasawa clarifies, homing in on what he and his KIKUSUI staff believe will set brewers apart in a market crowded with sake choices of roughly equivalent quality. “How do we shift focus from just making great products, to making meaningful ones? … We think our culture can be our greatest resource in pursuing both incredible sake and equally incredible experiences.”

Thusly, Takasawa says, the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute was born. The Institute has operated quietly since 2004, serving selected individuals with – alongside requisite tastings of small-batch and fresh sake – glimpses into sake history and culture, and KIKUSUI’s methods. Now, Takasawa has deemed it time for the center’s public debut.

KIKUSUI President Daisuke Takasawa

KIKUSUI President Daisuke Takasawa

Takasawa is a minor celebrity in the town of Shibata, Niigata prefecture – his birthplace and home to KIKUSUI’s main offices, brewery and the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute. His local fame is evidenced by the healthy turnout at the institute’s December 1 grand opening event; many in the crowd are locals who hang fawningly on Takasawa’s words and look genuinely excited to be taking part in what registers as a momentous event for the otherwise sleepy town of just under 10,000.

It’s standing before these locals and others who have traveled from further-flung Japanese lands that Takasawa pronounces goals for the institute much loftier than its cozy opening ceremony might suggest: to bring sake culture and education to the masses, regardless of personal provenance or prior sake knowledge.

The KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute boasts four distinct focal points: A tasting area, the Setsugoro Microbrewery, a museum of sake artifacts and a library bursting with books, materials and lore that represent all corners of sake knowledge.

Following Mr. Takasawa’s opening remarks and a mirthful kagami-biraki, cracking of a traditional cask brimming with fresh sake, guests proceed through each of these areas, contented by the masu of shinshu in hand from the freshly-malleted cask.

The tasting area is no doubt the star of the show for the thirsty visitors in the crowd, offering up an assortment of KIKUSUI’s famed Funaguchi sake cans and a number of very special labels – some available at the Institute on a rotating basis, others brought out specifically for this occasion. Of note are the 14BY and 19BY Ginjo Nama Genshu, the 15 and 10-year (respectively) aged sake were profound when experienced side-by-side. Both exhibit the bite and complexity of an aged drink, but the 14BY brings a noticeably funkier pungency that’s pleasant in a similar way to rich, umami-packed aged meats. These bottles are extremely limited in quantity and their presence here served as proof that KIKUSUI pulled out all the stops for this event catering primarily to superfans.

Guests also nibble on otsumami snacks that pair delightfully with the thimble-sized sake tasters. All present complementary and contrasting flavors to the sake at hand, but one – a spread of sake kasu, cream cheese and dried fruits – is delicious enough to warrant special mention and stands as a shining example of what this simple sake-making byproduct can bring to the table.

After the tasting, participants shuffle eagerly to the Setsugoro Microbrewery for a tour, glimpsing the facility’s inner workings through glass portholes that reveal sake craftsmen stirring, sifting and laboring in focused, quiet dedication. Sitting mostly belowground, the microbrewery itself recalls sake’s historical roots; manpower drives every step of the deeply traditional sake-making process at the Setsugoro Brewery. It’s refreshingly free of automation, providing a space for brewers to fine-tune recipes, and develop their skills and even their own identities as sake-makers.

The Setsugoro Brewery’s fermentation tanks; micro-sized in fitting with Setsugoro’s focus on small-batch brews

The Setsugoro Brewery’s fermentation tanks; micro-sized in fitting with Setsugoro’s focus on small-batch brews

Emerging from the brewery tour, what looks at first glance like a gift shop turns out to be a vast collection of sake artifacts, tools and serving ware from eras past. The impressive collection is anchored by a handful of genius Edo and Meiji-era devices that once facilitated the transport and even heating of sake and sake vessels, along with bento picnic meals. To imagine a blushing Meiji couple, enrobed in summery yukata and sharing a sip under the stars is to revisit a formative scene in present sake culture.

Just past this collection is the library, packed from floor to ceiling with very old texts and smelling invitingly musty the way any repository of history and heritage should. Participants in the opening ceremony are invited to peruse at their leisure and future guests will have this freedom, too. The vast majority of the texts are, unfortunately, in Japanese, but those that plan ahead for an English-speaking tour guide can surely glean all manner of hidden tidbits from sake’s past.

Both the artifact collection and the books are great attractions for those that want to immerse themselves in the essence of sake culture and provenance, but they, along with the innumerable similar items tucked away in the building’s storage vaults, are actively logged, examined and studied by KIKUSUI’s dedicated sake history researchers, who are here during the grand opening to provide helpful background and point out the most interesting finds. One such find is a jokey illustrated poster from the Edo period depicting kimono-clad women in the many hilarious states of sake drunkenness – preempting similar internet memes by a hundred years or more.

On the lower left is a vessel for rinsing sake cups. In center, a painting from the Edo era depicting the very same item (circled)

On the lower left is a vessel for rinsing sake cups. In center, a painting from the Edo era depicting the very same item (circled)

Sake’s past and present, its culture, heritage and future permeate the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute. Quite literally, it’s in the air; the interior of the low-sitting structure and its immediate surrounds that look out on Niigata’s distant, rolling mountains are fragrant with the yeasty aroma of fermentation.

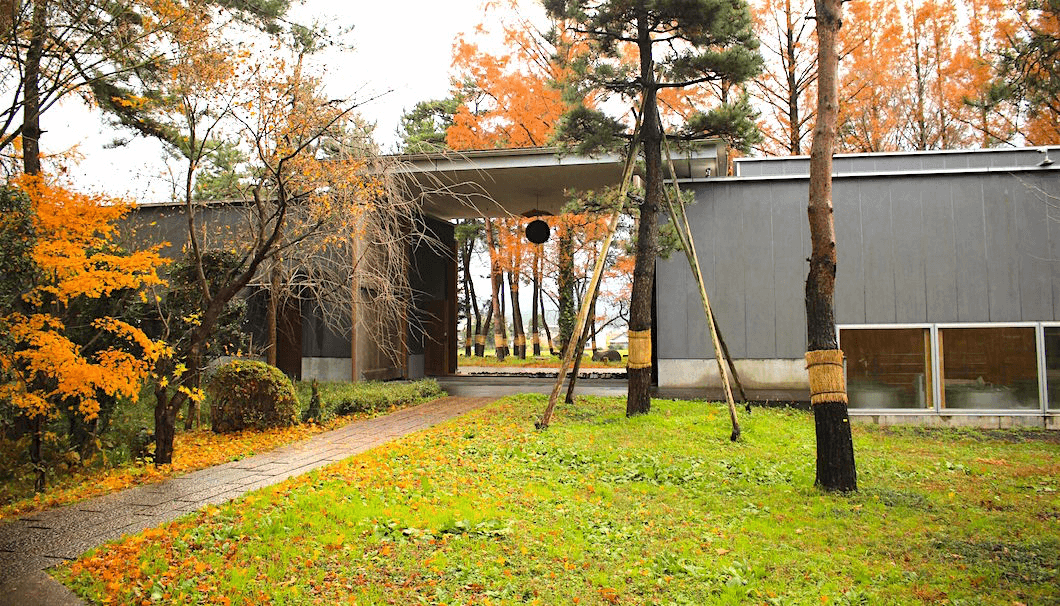

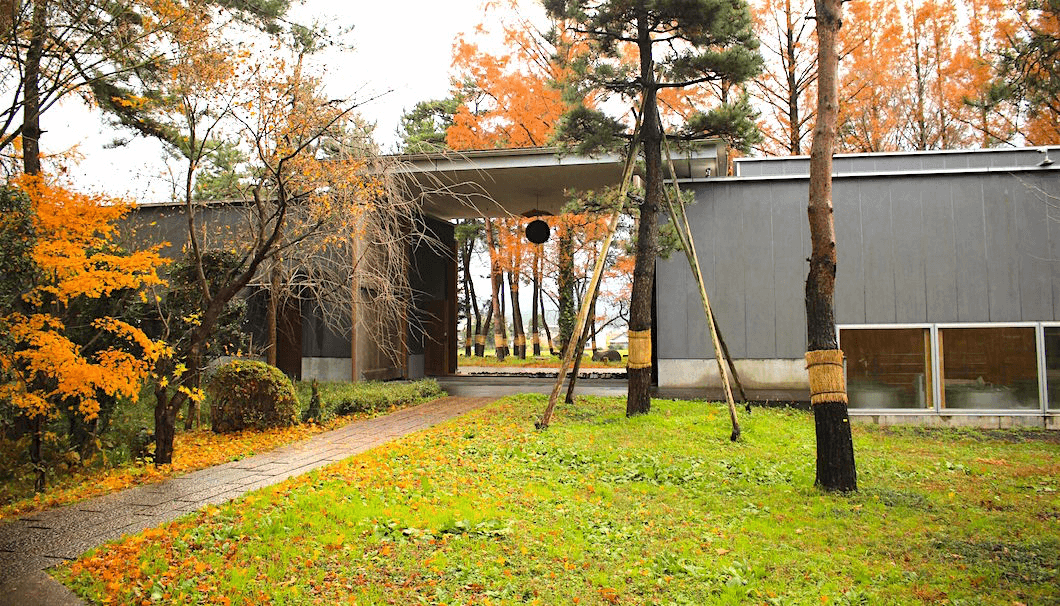

The Culture Institute, the Setsugoro Brewery and the KIKUSUI offices are tastefully designed and low-profile, blending seamlessly with the rice fields, the stands of trees dotting the grounds and, importantly, the community that KIKUSUI serves and is served by.

As the English home page for the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute notes, sake has played an integral role in Japanese culture and religion from antiquity. Historically, sake breweries like KIKUSUI have likewise served as pillars in the communities they occupy. Daisuke Takasawa himself – KIKUSUI president, with his local celebrity status – is testament that sake breweries still can and do serve to inspire their local communities. The Culture Institute and Mr. Takasawa invite one-and-all to become part of the sake community and experience sake culture up-close and firsthand.

Sake has long grappled with an image problem: that it’s a drink to be paired with Japanese food at Japanese restaurants – end of story. Sake enthusiasts know that’s not the case, and that sake can and should be paired with all manner of foods and scenarios. While this (criminally proliferative) misconception can partially be chalked up to western drinkers over-exoticizing sake as some kind of mystical far-eastern elixir, many brewers themselves are complicit in their slowness, even reluctance, to invite non-Japanese drinkers into the sake world.

The yeasty aroma of brewing pervades the air along this idyllic pedestrian path to the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute

The yeasty aroma of brewing pervades the air along this idyllic pedestrian path to the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute

It’s a breath of fresh air and a sign of changing times and blurring borders, that, according to KIKUSUI veteran Shu Watanabe, the company is already hosting foreign visitors to the Shibata company grounds, and is equipped to offer English language support to KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute visitors who need it – provided they kindly call ahead.

KIKUSUI’s willingness to include non-Japanese enthusiasts in the sake conversation is further exemplified by Mr. Takasawa, who, when asked what future scenario he envisions for sake internationally, replies: “I picture [western households] with a bottle of sake on the table at family dinner time. Like it’s a given.”

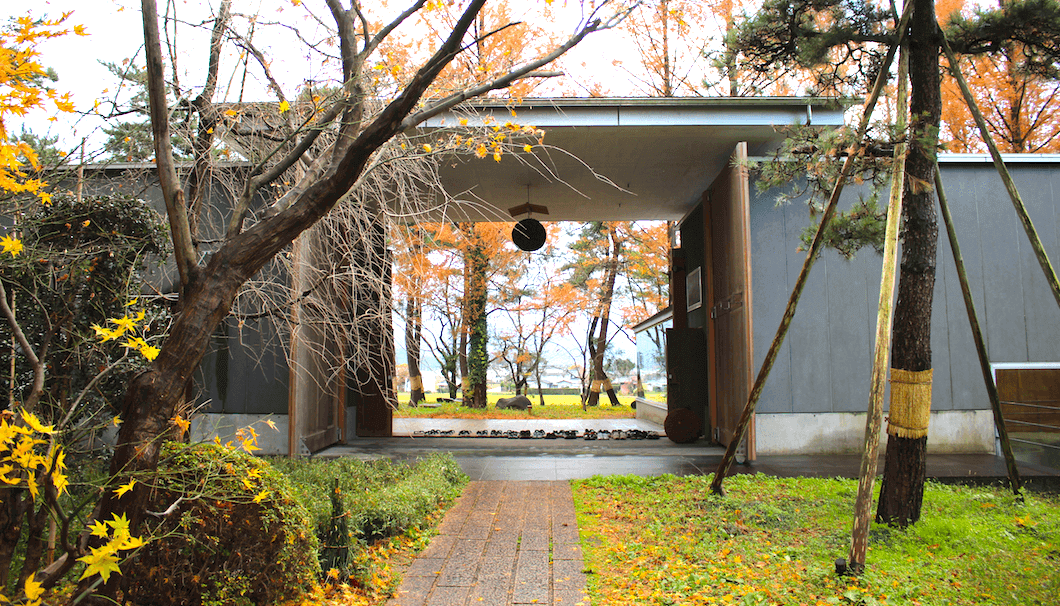

In the Culture Institute’s central awning, a fresh sugidama.

In the Culture Institute’s central awning, a fresh sugidama.

Due to the fortuitous timing, as guests exit the KIKUSUI Sake Culture Institute, they happen upon a unique and somewhat uncommon sight: a sugidama ball of cedar branches, freshly hung from the ceiling of the outdoor foyer leading into the facility, and the dried husk of the previous sugidama lying in contrast on the ground nearby. The sugidama traditionally serves as a kind of hourglass for sake brewing, hung anew at the beginning of a brewing season, its gradually browning branches keeping time throughout the brewing season.

Here, viewed in juxtaposition, the new and old sugidama conveniently encapsulate the goals of KIKUSUI and the meaning behind the Sake Culture Institute – a new brewing season has begun, except from here on out, everyone is invited to take part.

Comments