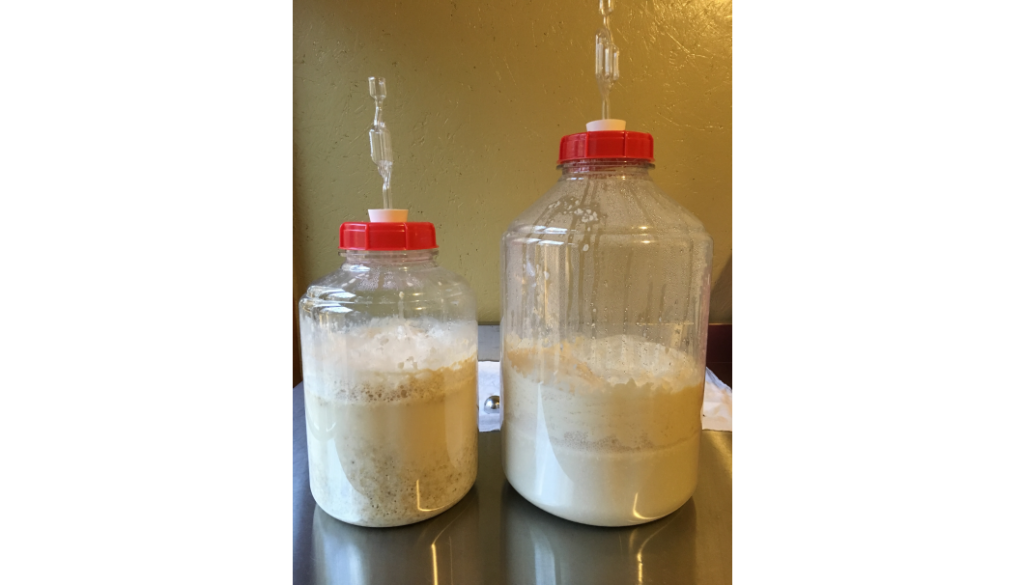

Doburoku is a cloudy beverage with a cloudy legal history. Doburoku is like a nigorizake as it retains some lees (kasu). While a nigorizake goes through the same brewing steps as a clear sake, doburoku makers combine all their ingredients at once, and usually don’t press their product as thoroughly as a standard sake, if they do so at all.

Doburoku’s legality also stands in something of a gray area. Brewed at home, as it had been for centuries, doburoku was declared illegal in 1899. But, since the government today does not consider doburoku to be a sake, it’s easier to obtain a license to make it commercially than to produce actual sake. Recently, licensed doburoku brewers are transforming a beverage long associated with clandestine homebrewing into a product for new microbreweries and brewpubs.

Homebrewing in Japan

Homebrewing has a long history in Japan. Excavations of the residence of the prominent politician Prince Nagaya (684-729) revealed he employed a staff of brewers and even sold some of his product in the city markets of Nara. Homebrewing must have been prevalent in the medieval city of Kamakura in modern Kanagawa Prefecture because a survey in 1252 found 37,274 sake pots in private residences — more than one for every two people living there. After a commercial market for sake and doburoku developed by the early modern period (1600-1868), Edo (present day Tokyo) found itself unable to compete with the breweries of Nada in modern Hyogo Prefecture, but Edo was home to numerous doburoku makers. One 1837 survey estimated that each of the city’s wards had one or two doburoku shops. Despite the efforts of the shogunate to curtail the doburoku trade, the number of shops remained consistent in the 1800s, and an 1872 survey still found one or two doburoku producers per ward.

In the Meiji period (1868-1912), taxes on sake breweries became the government’s main source of revenue in the late nineteenth century and that affected laws on homebrewing. Initially, the Meiji regime exempted doburoku makers from control and taxes. But, thirsty for more revenue, the government gradually increased taxes on sake and tightened restrictions on homebrewing, prohibiting it completely in 1899.

Despite being made illegal, doburoku refused to disappear. Doburoku production in Iwate, Miyagi, and Akita Prefectures remained on par with sake in 1886 and that year nine times the amount of doburoku was made in Kagoshima Prefecture compared to sake, according to scholar Fujiwara Takao. Through the Second World War and the era of Japan’s high-speed economic growth in the late 1950s and early 1960s, illegal homebrewing quietly continued. Today, a few stores and religious institutions have special permission to brew doburoku legally, as Alisa Wylie describes in her SakeTimes article. Anyone else caught making a beverage over 1% ABV without a brewing license faces up to a decade in prison and a one million yen (approx. $8,700) fine.

Activist Maeda Toshihiko (1909-1993) sought to challenge this prohibition, and he published a book in 1981, Let’s Brew Doburoku (Doburoku tsukurō), which led the government to charge him with brewing without a license. Maeda argued that the Japanese Constitution recognized his “right to the pursuit of happiness” that included homebrewing for personal use. A lower court found Maeda guilty in 1986, but he appealed his case to Japan’s Supreme Court. Although the high court ruled against him in 1989, Maeda’s book became a bestseller.

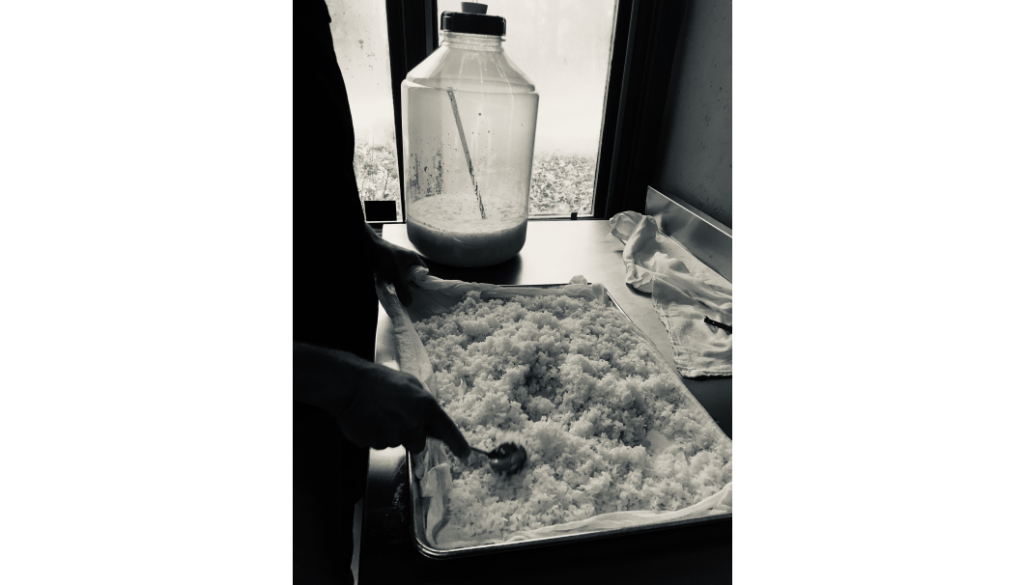

From the mid-1970s to 1999, one of the most important magazines for Japanese farmers, Modern Agriculture (Gendai nōgyō), ran a series of articles that featured homebrewing techniques from around Japan. Many examples were variations of the basic doburoku recipe in which the rice, koji, and water were combined simultaneously, but some methods were more complicated and followed the same sake brewing technique of adding the ingredients in stages.

One homebrewer in Iwate Prefecture showed how to make doburoku from barnyard millet (hie) and foxtail millet (awa). Readers could also learn how to brew doburoku from long grain rice from Southeast Asia or from leftover mochi rice cakes. A contributor from Kumamoto Prefecture shared how he was able to make doburoku in the wintertime by the traditional method of burying his sake pot in a pile of cow manure, which naturally heated the ferment. The series made clear that many folks were creatively continuing traditions of homebrewing despite it being illegal.

From Homebrew to Microbrew

Brewing doburoku without a license is illegal but obtaining a license to do so is easier than getting one for sake brewing. A license to brew sake requires having the capital and equipment to produce 60,000 kiloliters annually from the start. However, a license for doburoku only requires the capacity to produce six kiloliters annually. Doburoku, in other words, provides a legal way for entrepreneurs to create a sake-like beverage on a smaller scale, and in the last several years micro doburoku brewpubs have opened in Tokyo and other parts of Japan to take advantage of that. One of these pioneer breweries is Wakaze, which opened in Setagayaku in Tokyo in 2018. Wakaze produces doburoku for sale and to serve at its micro-restaurant of nine seats. Wakaze also opened a sake brewery near Paris in 2019 and plans to open a restaurant in Paris in May 2022. Konohana Brewery is another Tokyo doburoku brewery. It opened in Asakusa in June 2000, promising “a new era for doburoku” in its own label, Hanagumori.

Doburoku has entered a new era, coming out of the clandestine world of illegal homebrewing and passing through a legal loophole that makes it much easier to manufacture for sale than sake. Customers of these micro doburoku establishments can now discover the cloudy beverage that householders crafted for centuries and perhaps still sip secretly today.

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments