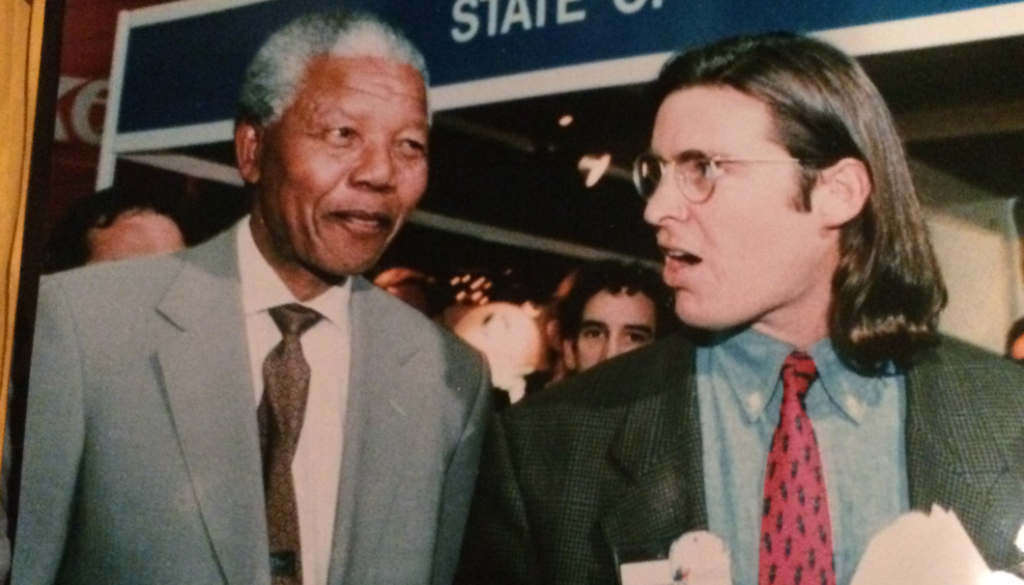

Seeking a bit of privacy and quiet for his video call with SAKETIMES, sake sommelier and business owner Beau Timken has ensconced himself in his daughter’s room. She’s newly away at college, but her soccer trophies and collected bric-a-brac of high school mementos remain, providing a slightly off-kilter background for a scruffy middle-aged man with light shoulder-length hair tending towards grey and a gruff countenance.

As one of the premier merchants for Japanese sake in America, one might expect Timken to have a slick, salesman-like persona, but that expectation might be a little off base. He’s direct, even brusque, at times, with a penchant for that particularly American brand of no-holds-barred straight talking. It’s a bravado that has served him well in a mission of carving out a valued place for sake in America’s drinking landscape.

“Look, sake found me. It came to me,” he says. “I didn’t find it, it found me.”

As a young college student in California in the late 80s, his exposure to sake was limited to the artless ‘hot sake’ sometimes found at American restaurants. He liked it but wasn’t especially enamored. His exposure to what one might call ‘real’ sake came a few years later when he was working in South Africa.

“I went to a sake restaurant and there were two captains of fishing boats, drinking something… As people do in sushi bars, [we] start talking.” Timken was drinking hot sake and he thought they were drinking wine because they were pouring something chilled they’d brought themselves. But actually, it was a premium sake and the gracious captains let Timken have a taste.

“I had that moment with the jaw drop, and the guy looked at me and he said, it’s the same. But it wasn’t the same. What they were drinking and what I was drinking weren’t the same. So my brain took off and I went home and I started a journal. I’d never had a journal in my life. And I wrote down: how could rice and water taste like honeydew melon?”

From this simple rhetorical, Timken’s explorations spiraled outward into the vast world of sake. Finding an answer to one question inevitably led to several more, but this was in the days of dial-up internet and there wasn’t much information available online in English anyway. So he had to do things the old-fashioned way: by talking to people who knew a little something.

“It was always the sushi chefs at different sushi bars that I would go to that were my educators. And they all came from different prefectures and they all loved their prefecture’s sake, so they would guide me,” says Timken. “They would share with me and explain the categories and explain milling rates.”

When he returned to San Francisco, he explored the shops in Japantown, asking staff about the sake on offer. He wrote letters to sake specialists making a name for themselves in the English world, like John Gauntner. He didn’t hesitate to approach anyone who might be able to teach him something new about sake.

“I was a street fighter,” Timken says. “I learned sake on the streets because there were no great sake courses out there. There were no education programs.”

But learn he did, eventually traveling to Japan to visit sake brewers and pick up a Kikisake-shi certification while he was at it.

Meanwhile, although interest in sake and Japanese food in general was increasing Stateside, Timken often found shop staff, waiters, and even distributors in California couldn’t tell him much about the product they were selling. Timken realized there was an opportunity to bridge that gap, educating consumers and selling premium sake with the care and attention it deserved. The result was True Sake, America’s first dedicated sake store, which Timken opened in San Francisco’s fashionable Hayes Valley neighborhood in 2003.

The main competition in California was the wine market, where snobbery and expert evaluations of quality were sacrosanct. But Timken wanted sake drinkers to have more freedom to embrace the sake they enjoyed regardless of what others thought.

“I was a self-taught guy and it gave me confidence, 100% confidence, because… I’m the champion of my palate. I like what I like. Nobody can tell me this is good or this is bad,” says Timken.

This philosophy is reflected in True Sake’s reviews, eschewing rating systems and other qualitative evaluations in favor of describing flavor profiles. Customers can then choose the kind of sake they like rather than worry about whether it’s considered ‘good’ by the powers that be. And for new acolytes, the reviews even mention comparable wines and beers to provide helpful signposts for what they might enjoy.

This anything-goes approach might sound very laissez-faire for someone whose role includes sake education, but while Timken wants his customers to be free to like what they like, he also demands they take ownership of those preferences, that they develop their palate and try to understand sake better.

“Traditionally, American sake consumers were lazy. They can remember a German beer name, a French wine name, but the curtain went down with anything Japanese,” says Timken, recalling customers coming in to look for sake they’d had with only the vaguest of descriptions.

So True Sake instituted a customer profile system in which customers were asked to evaluate the sake they had previously purchased. This helped staff recommend new sake, but it also created accountability.

“I beat my customer base up too, you know. I make them work for it,” says Timken. “Those [profile] books were a way to get them to work. They had to grade, to go home and think about it. They weren’t going to go home and just drink it. They’re like, ‘Oh crap, I have to go back to Beau and tell him something.’ You’re damn right you do. You’re going to have to tell me because I need that grade.”

Customers seem to appreciate that chivvying along, as the system has expanded from a few notebooks behind the counter of the brick-and-mortar store to a digital system that encompasses True Sake’s online store as well. There are now some 42,000 registered users, over a quarter of which are returning customers. To date, True Sake has sold some 1.5 million bottles of sake.

This retail strength also allowed Timken to push for changes from distributors.

Timken would refuse sake that had been warehoused for too long, pushback American distributors weren’t necessarily used to, and asked for bottling dates to be printed on the labels. He also consulted with distributors on other aspects of labeling, encouraging them to add romanized names and even English nicknames for the brewers, for example. Americans might have difficulty remembering Kokuryu, but Black Dragon is easier to recall, the logic went.

Even beyond the immediate needs of his own business, Timken felt he needed to drive distributors to expand their reach and create a larger presence for sake. For a long time, sake had been treated as a small sideline; a niche product. But Timken wanted every restaurant that had a wine menu to have a sake option because he knew it was versatile enough and that there was latent demand.

“A lot of times, years ago, the Japanese sake business was lazy,” Timken says, noting reps from the motherland would stick to, “Just sushi restaurants or ramen houses. They weren’t shaking the trees and beating the bushes to put sake in Western restaurants.”

The long years of outreach and education have borne fruit. Many of the changes he pushed for have since become commonplace in the industry and sake gets more readily available and more popular every year. According to Japan’s Ministry of Finance, the US imported 3,014 kiloliters (kL) of sake in 2009. A decade later that’s more than doubled, with imports reaching 6,452 kL in 2019. Additionally, there’s a growing amount of domestic production from small craft brewers and American facilities run by big names like Gekkeikan.

We ask Timken whether the recent pandemic, which has hit food and beverage industries particularly hard, has presented setbacks in this burgeoning popularity.

While not wishing to diminish its terrible human and economic costs in any way, Timken says COVID has had some positive impact on his industry. “It provided us a stress test. You need stress once in a while in an industry. And the stress test came in the form of, ‘Holy crap!’ these guys are like, ‘all of our accounts are restaurant accounts, not retail accounts.’”

So distributors realized the necessity of developing diverse sales channels as they hustled to move the product they had on hand. Timken says the smart ones will also think about how they can plan for future shortages and interruptions, not only for their own business but because market shocks travel up the production line, affecting brewers, rice farmers, and even tertiary businesses like packaging manufacturing. The result will be an industry that is more agile and better able to weather future challenges.

Meanwhile, True Sake’s and other retail outlets’ sales have hit record highs as more people choose to drink at home. Adding door service has allowed them to safely meet that need, reaching new customers looking for something novel to explore during idle time, helping distributors move product that had been destined for shuttered restaurants, and providing jobs during a difficult economic time by expanding staff.

After nearly two decades in the industry, Timken says the experience also showed how essential it has become for American fans, leaving its old sushi bar stereotype far behind.

When True Sake was briefly closed by government-mandated shutdown, Timken said, “So many people reached out to us, like, ‘Beau, I need your product. It’s going to help me get through this.’ …So we went back to work.”

That is compelling evidence that he’s been successful in helping to establish a sake culture on American shores, but we ask if he has any big goals still remaining. He says he still holds on to one big unrealized dream, something that will show him sake has truly become part of the mainstream, has integrated itself completely into American life: to see sake advertised during the Super Bowl.

That’s how we’ll know that the West has indeed been won.

Comments