From Zero to Sake In Record Time

Born and raised in Canton, Ohio, American Beau Timken ran a business in Capetown, South Africa in his younger years. It was here that a chance encounter with some Japanese fishermen would spark a lifelong love affair with sake.

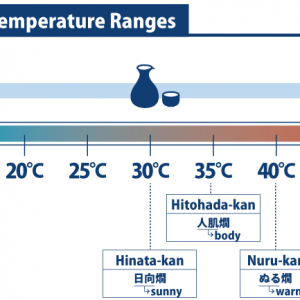

“Up until then, I had only known hot sake,” Timken told SAKETIMES of his first experience with the drink served chilled, as is often intended in sake’s native Japan. “I was wondering if they’d just forgot to heat it, but then was shocked by it! It tasted like honey and melon even though none of that was in it! That ginjo sake changed my life.”

After his time in South Africa was complete and he returned to the USA, Timken was still fascinated with sake and set out to learn more about it. At the time, though, the internet was still in its infancy and there was very little English writing on the subject.

“In the absence of any information, I tried to pick it up on the street,” recalls Timken. “I went to a bunch of sushi places and spoke with the chefs. I learned a lot that way, but to really understand it I needed to experience it firsthand. Before even knowing what ‘nihonshudo’ was, I had developed my own personal scale of sweet and dry sake.”

His pursuit of sake knowledge brought Timken to meet John Gauntner, one of the world’s leading non-Japanese authorities on sake, who also hailed from Ohio. From there, Timkin was inspired to travel to Japan and visit the breweries of sake’s birthplace in order to learn more about the process. It wasn’t long after that that Timken was certified as a kikisakeshi (sake sommelier).

Ignorance of Sake is Not Bliss

Having acquired a treasure trove of knowledge about sake from his time in Japan, Timken was faced with the dilemma of how to use it. Inspiration came when he was visiting a Japanese supermarket in San Francisco and asked a clerk the simple question: “What do you think of this sake?”

When the clerk was unable to reply, it dawned on Timken that there was a severe lack of knowledge among sake retailers in the United States. If there was no one who could explain to potential customers how and why to drink sake, then it would certainly never gain any traction among American drinkers.

So, much like those fishermen did for him, Timken set out to shatter people’s preconceptions and misconceptions about sake, and show them what they’ve been missing all this time. In 2003, Timken’s own store, True Sake, opened its doors for the first time.

True Sake

For 17 years now True Sake has graced Hayes Valley, San Francisco – nestled among the area’s many fashionable boutiques, cafes, and restaurants. Anyone walking through the fanciful Patricia’s Green art park should be able to spot its distinctive blue sign and sugidama (balls of woven cedar used by Japanese sake breweries) hanging in the entrance.

“America’s First Sake Store” is written on the window, and even now there isn’t a store quite like it anywhere. Timken knew that there would be many Americans, like he once was, who didn’t drink sake simply because they didn’t know enough about it. These would be his target customers.

That was no easy feat though; at the time, the general consensus among average Americans was that sake was a shot drink because it had too much alcohol. On top of that, there were the bottles with labels written in esoteric Japanese that Americans couldn’t even read let alone begin to understand. Breaking down these barriers was going to be a challenge, but one Timken and True Sake was up for.

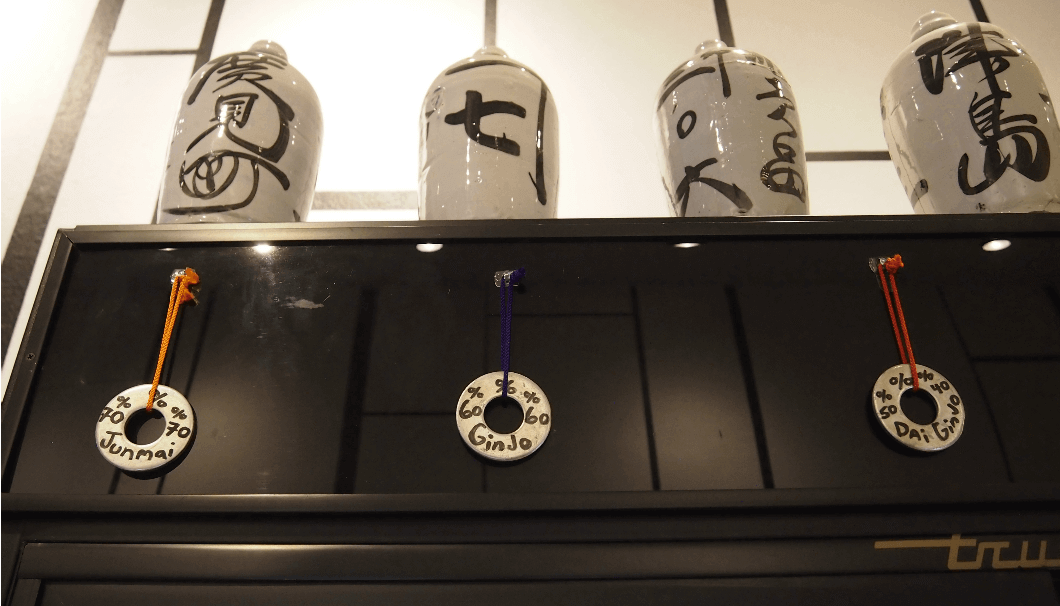

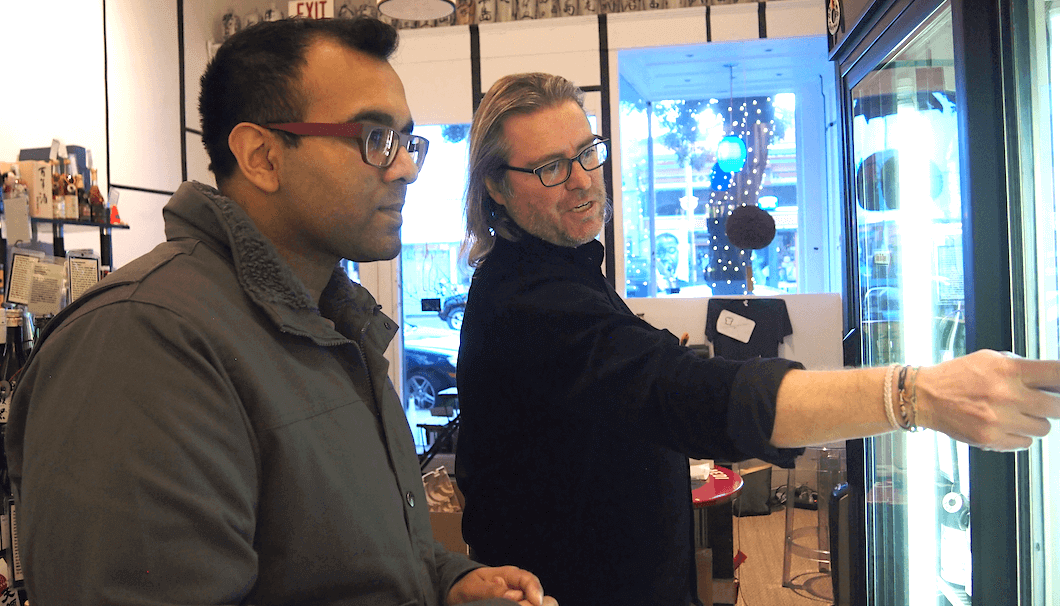

The store is roughly 38 m² (400 ft²) and holds about 300 different brands. However, offerings change seasonally, resulting in a dynamic lineup. While great for sake aficionados, this is overwhelming for newcomers. But True Sake minimizes the confusion using color-coded ribbons to distinguish different types, like ginjo from junmai daiginjo bottles. There are also comparisons to more well-known brands and explanations in laypeople terms.

Another problem is that English-speakers have trouble remembering the Japanese names, so even if they really liked a particular brand, they might not be able to recall it on their next visit to True Sake. To combat this, Timken started a customer profile system to keep track of what they bought in the past and how they liked it.

“There were four velvet books behind the cashier counter. So for example, if a customer says, ‘I’m Grey 178,’ I’ll take out the grey book and look up the page with their number,” Timken explains. “Then I say ‘Oh, you bought this sake from this brewer. How was it?’ and based on their past answers I would recommend something. It’s important that the customer evaluates for themselves.”

When Every Day is Sake Day

After hitting about 600 regular customers, True Sake updated their books to a computer system. In addition to its visiting customers the store has also gotten into online sales, delivering to 42 states, with a newsletter sent to about 20,000 subscribers.

Timken has never forgotten the power of community outreach either. Every October 1, which is known as Sake Day, True Sake holds a tasting event that highlights 250 domestic and international brands. In 2019, a record 900 people came out for it.

When the store opened in 2003, global sake exports from Japan totalled 3.9 billion yen (US$36M). Now, after ten straight years of growth, the amount has expanded six times that. The rest of the world was finally beginning to learn what Beau Timken had on that fateful day in South Africa.

But he is far from satisfied, and believes that sake still hasn’t reached its full potential: “I’m not going to rest until I see sake advertised on the Super Bowl. Sake’s future has not been determined yet, and that’s a great thing. No one knows what’s going to happen and that means sake can still become the king of liquor around the world.”

After seeing what a lone store in the USA has already accomplished, Timken’s vision for the future may just come true someday.

Comments