Rice is the heart of sake brewing, but with the aging of Japan’s farmers and a shaky economy further struck by the Covid-19 pandemic, the future of sake rice looks increasingly murky. While the industry limps along in uncertainty, a movement to corporatize Japanese rice agriculture may hold the key to its survival.

The State of Sake Rice Farming

The pandemic has had an undeniable impact on sake rice farmers. Sake sales dropped drastically in 2020 and 2021, leading to excess stock, and a slump in rice demand. As one example of the dire circumstances facing rice makers, Hiroshi Kiriyama, head of Hyogo’s Japan Agriculture (JA) Rice and Grain Division, was quoted as saying that nationwide demand for Hyogo-grown Yamadanishiki is down 25% from 2019. An April, 2021 report from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) entitled “Information About the Sake Industry” (Nihonshu wo Meguru Johyo) showed similar data, concluding that between the drop in demand, recent production growth, and current surpluses, farmers should limit production for the 2021 growing season to 80% of previous years.

A representative from MAFF’s Crop Production Bureau tells SAKETIMES that this limit is just a recommendation, and there’s no legal way to force farmers to plant less rice. At the same time, MAFF is working with JA—the main channel for individual farmers selling rice to sake breweries—and with individual Japanese prefectures to persuade farmers to listen to the advice. Without demand, any rice they do grow will sell at drastically reduced prices, or not at all. No matter the path, though, this will inevitably lead to some loss in income for farmers, the representative says, and there is no direct financial support to make up for it. Rather, the government is offering subsidies to encourage switching to crops with higher demand—for example soybeans, wheat, and rice for animal feed or industrial use.

Covid’s impact on Japan’s agriculture isn’t the industry’s biggest issue, however.

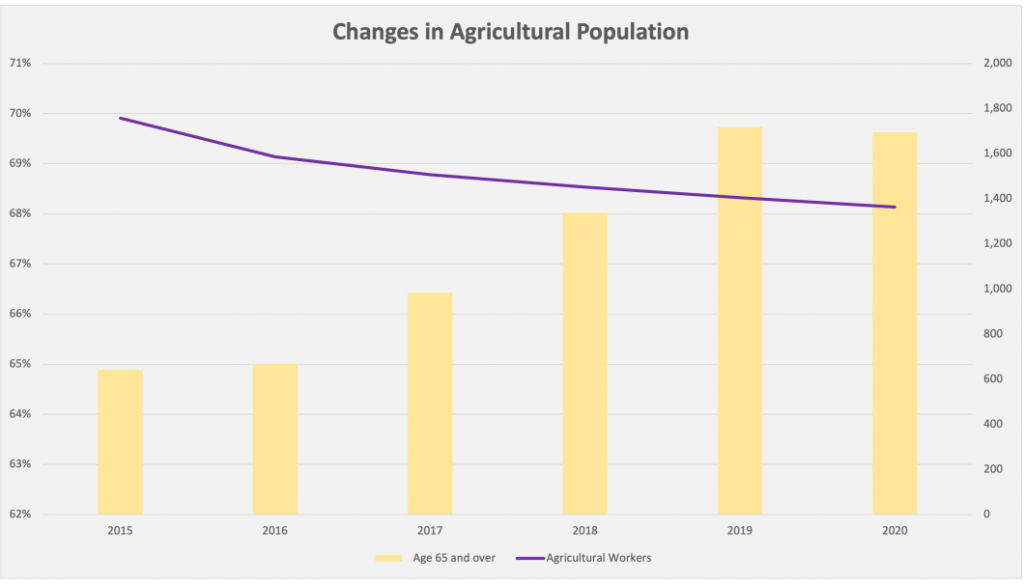

Speaking with SAKETIMES, Shodai Yamazaki, a rice procurer with the Yamaguchi Prefecture branch of JA, says, “The pandemic has caused demand problems, but even before that, last year’s rice crop was one of the worst ever due to pests and inclement weather, so farmers were already suffering from lower income. The biggest issue, though, is that farmers across Japan are on average growing older. Many are already near retirement age, and all these problems coming at once are killing their motivation.”

When those farmers do call it quits, many have no one to take over their fields. Often when these farmers retire, their fields essentially retire too, diminishing Japan’s rice production capacity.

Going Corporate is Key

Enter the agricultural corporation. These companies, usually formed by a farmer with an entrepreneurial bent, take over fields that the original owners can no longer work. They then employ individuals to farm these newly acquired fields as a salaried job.

JA’s Yamazaki notes that recent years have seen a surge in the practice. Takahiro Nagayama, brewery manager of Nagayama Honke Shuzojo brewery and CEO of agricultural corporation Domaine Taka, says that one of the reasons he founded that company is to ensure a future for local agriculture.

“Aging is a huge problem here,” he says, because, “all the younger people have left for the cities.” To reverse that trend, he explains, will require agriculture to become an attractive career choice. “No one will be willing to take over fields if we don’t have an organization that pays salaries and provides a stable working environment.”

Farm Tsuru no Sato is a farming corporation in Yamaguchi’s Yashiro region. CEO Iwao Onaka tells SAKETIMES that the company currently manages around 40 hectares of fields for local farmers. Yashiro is a farming community in the mountains of Shunan City, where many of the farmers are well into their 70s and can no longer handle the hard labor of farming. Tsuru no Sato plants their fields with table rice, soybeans, barley, and also Yamadanishiki for sake brewing. The company has eight full time employees, and apart from the CEO, all are in their 30s or 40s. Onaka goes out of his way to recruit younger people to come to Yashiro and take up the job. One of those employees is Shintaro Jinda, the current head of the company’s Yamadanishiki fields, and at 34 years old, one of the youngest farmers in the area.

Jinda came on board as a full time employee on recommendation from a friend. He had not been a farmer before, but was involved in the rice business as an inspector. He feels that the corporate approach to farming is a net positive.

“It’s good that farming is changing from the old way, where it was only a family business and you couldn’t choose whether or not to be a farmer,” he says. “We should let people do what they want, because the ones who actually want to do the work will be better at it.”

But how do these corporations find people who want to do the work, like Jinda? A stable income seems to be one possible answer. Nagayama comments, “If we don’t incorporate properly… and make farming a salary-based business, I don’t think the younger generation will ever enter the farming industry again.”

Have a Drink for the Future of Japan’s Rice Farming

As with any business, agricultural corporations need profit to pay those salaries. Sake rice in general, and Yamadanishiki in particular, is popular, despite its notorious cultivation difficulty, precisely because of its high income potential.

“We only have 2.1 hectares of Yamadanishiki right now, but we are ready to plant more if the demand is there, even though it falls over so easily,” says Onaka. “Because it sells for so much!”

MAFF data shows that the 2020 price for Hyogo-grown Yamadanishiki was ¥23,700 (approx. US$215) per 60 kg unit, compared to an average of ¥13,837 (US$125) for common table rice. Even with the harder work involved, that huge price difference is incentive for both individual and corporate farmers to make the effort, but only if the rice will sell.

An increased demand for Yamadanishiki, and other high-priced sake rice varieties, will help build stable income for these farming corporations, and so create an attractive working environment for young people. In other words, drinking more sake is one clear way to help support a future for Japan’s farmers.

*We are sending you monthly updates and the information. Register here.

Comments