The premium sake boom that started in the 1990s kicked off a race to the bottom in rice milling as breweries competed to release super-premium sake using increasingly highly-polished rice. Others, though, have looked another direction, reasoning that less polished rice can lead to less waste and more interesting sake. This approach, while novel in today’s sake landscape, brings challenges as well as opportunity.

The Sake Milling Arms Race

Although premium sake like ginjo and daiginjo date back to at least the 1970s, the Japanese government introduced its modern classification system in 1989, finally giving legal definitions to individual sake styles. One key figure in this regulatory system is “seimaibuai,” or rice milling ratio. This number represents the percentage of rice grain left after the outer layers are milled away during the brewing process. When authorities set minimum polishing rates for sake to qualify for higher grades, it created a simple measure of sake quality that both drinkers and brewers took to. As sake sommelier and educator Marie Chiba put it in an earlier interview with SAKETIMES, “Numbers like the milling rate are easy for customers to understand,” increasing the attraction for both buyers and sellers.

Many sake brewers have since given seimaibuai a prominent place on labels, and have competed over who could achieve the lowest. Hiroshi Sakurai, former president of sake maker Asahi Shuzo, describes the 1992 birth of the company’s Dassai 23 label on the official brewery website as the result of just such a competition: “It was first planned out to be polished down to 25%. I waited for the rice to begin the polishing process, before going on a business trip. This is when somebody told me a major producer from Nada [Ward, Kobe] was already selling a Junmai Daiginjo sake polished down to 24%… I phoned my staff, asking them to polish the rice 2% more, down to 23%.”

The competition continued, with Niizawa Shuzo brewery releasing a sake from rice milled to 9% in 2009, eventually bringing that number down further to 7% in 2016. Of the increasingly fierce competition, in his book, The Sake Bible, sake writer Brian Ashcraft says, “Things had turned into the sake industry equivalent of the arms race. Tatenokawa, the first junmai [daiginjo]-only brewery in Yamagata Prefecture, released its own 7% super-premium sake called Shichiseiki… in 2017. That same year, Tatenokawa released a sake with a 1% polishing ratio called Komyo.”

Niizawa eventually responded with what must be the final shot of the milling war: a 0% seimaibuai sake known as Reikyo Absolute Zero. The actual rate is 0.85%, but a technicality in the laws allowed fractional milling percentages to be rounded down, meaning Niizawa could technically claim the seemingly impossible 0% on labels and other documentation. The government closed this obvious loophole in 2019, rendering 0% polishing ratios rightfully impossible once again.

Another Way

Not everyone embraced low seimaibuai numbers to such ludicrous extents. In fact, some, both inside the industry and out, have expressed concern over excessive polishing; perceiving it as disrespectful of the rice-growing industry, and wasteful.

Justin Potts, host of the Sake on Air podcast and longtime industry veteran, shared his thoughts about this issue, saying. “A lot of producers are just now putting into practice the realizations that many have been harboring for some time, which is that the industry as a whole might have left some very viable and equally high-quality style options behind during an extended period of tunnel vision. The exception to that might be the handful of breweries that are critically reexamining how some production choices are intrinsically tied to the sustainability of related agricultural, environmental, and business practices.”

He elaborated on the polishing focus, adding, “Several of the standards that have largely gone unquestioned as ‘best practice,’ or that were generally assumed to be a necessity for the creation of a rather narrow view of ‘good sake,’ are arguably somewhat excessively resource- and energy-intensive, when maybe they don’t necessarily need to be.”

Chiba Prefecture brewery Kidoizumi Shuzo has stayed out of the polishing race from day one. Although best known for its “hot yamahai” starter method, in which it creates a fermentation starter using 60℃ water and natural lactic acid bacteria, the brewery also staunchly avoids highly polished rice as a matter of course. Kuramoto (brewery owner and manager) and toji Hayato Shoji also spoke to SAKETIMES about his brewery and its low milling rates: “We adopted a totally new way of brewing sake in 1956 using high-temperature yamahai starters,” he says. “We have used that method ever since, and at the same time, none of our production sake uses a seimaibuai below 60%.”

They find that the less polished rice matches their style, he says, but just as importantly, “rice is a valuable ingredient, grown with such care by the farmers who work with [Kidoizumi]. It seems wasteful to polish so much of it away. We hold more respect for our ingredients.”

Shoji says that he’s experimented with other mill rates, if only to test the possibilities. “We have done one batch of sake polished to 30% to celebrate the end of the Heisei period in its thirtieth year, and two test batches in the 50% range, but we really think that 60-65% is the best range for us.” He’s also gone the other direction when it comes to milling: “We have done some 90% batches, and this year we did a whole grain batch.”

Whole grain sake, called genmaishu in the industry, is rare. A Google search only offers up three products. The process is challenging, Shoji says. “We couldn’t get koji spores to grow on the whole rice at all, actually, so we had to polish the rice for koji to 95% just to get the husk off. All of the mashing rice was whole grain, though. It fermented very quickly because of all the rice nutrients in there. It was only in the tank for seven days.” A typical fermentation for sake lasts at least 20 days, and for ginjo styles, can drag on more than 30. That led to changes in the brewing process, and increased pressure on the brewery, Shoji adds.

Market Full of Big Numbers

Despite the challenges that less-polished rice may bring, many sake brewers now have sake on the market with seimaibuai numbers far bigger than 60%. Izumibashi Shuzo has its Megumi Ebina Gochi, with a seimaibuai of 80%. Kikuchi Shuzo in Okayama Prefecture offers a junmai sake made from Omachi rice milled to just 80% as well. Fukui Prefecture’s Mikawa Shuzojo has a regular production brew under their Maibijin label at 85%. Other breweries that have regular production sake in the 80-90% range include Tsuchida Shuzo (Gunma Prefecture), Onda Shuzo (Niigata Prefecture), Umetsu Shuzo (Tottori Prefecture), and many more.

Percentages above 90% are more rare, but still available. Tochigi Prefecture’s Senkin has set its entire “Organic Nature” line at 90%, and Moriki Shuzo has a junmai with a 90% mill rate under the label Tae no Hana Challenge 90. Yoshikawa Toji no Sato brewery has a 90% sake, called Arigatashi Junmai, as well. Some breweries, like Sakai Shuzo in Yamaguchi, offer limited brews in this range. Sakai releases around 300 bottles yearly of its sake “Ride? Black” label that uses a mill rate of 96%.

Then, there is the elusive genmaishu. Apart from the aforementioned batch from Kidoizumi, Terada Honke makes a regular production brew called Musuhi from 100% unpolished rice, but instead of using koji, it actually malts the rice, germinating it to release the enzymes needed to make sugar from starch. This means it is not technically seishu (the legal name for sake), but is nevertheless otherwise brewed exactly as any other sake. Akashi Sake Brewery also makes a genmaishu, Akashi-tai Genmai Yamadanishiki, and its website brings up an issue of particular note with the style: taste. It says that in taste tests, only five out of a hundred people said they enjoyed the flavor of genmaishu, while sixty said it was “not for them.” That may explain why a representative said that, while the brewery still makes genmaishu, sales are on a limited basis only.

With more and more sake with big seimaibuai numbers on the market, Hayato Shoji offered his thoughts about the trend’s future: “The milling race is over. With a 0% out there, there’s nowhere else to go. The time to focus on something different has come. I think that there will always be highly polished sake on the market, but now people are finally ready to accept another style as well.”

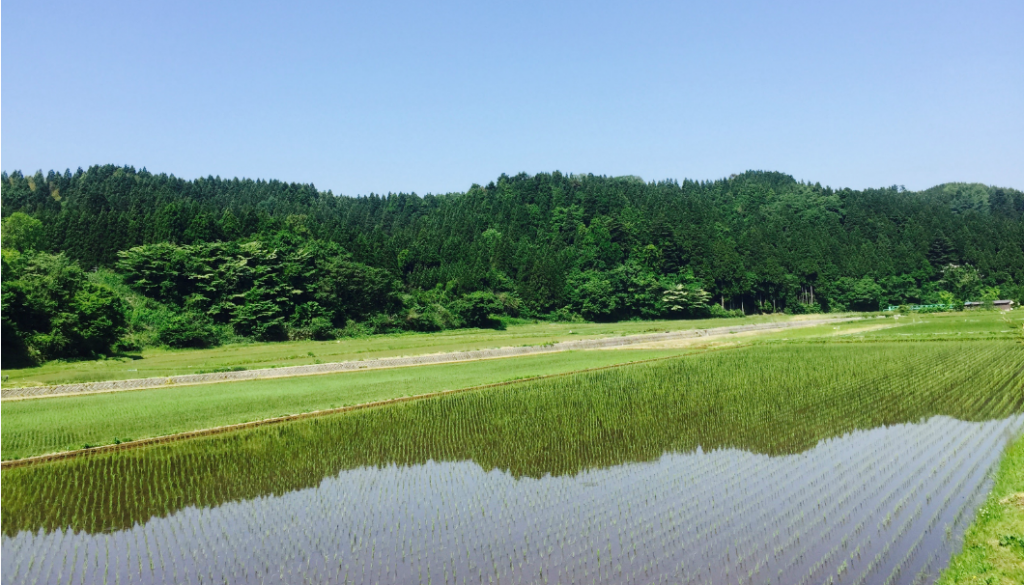

*Top Image: Photos by JUU Food, Photos provided by Kidoizumi Shuzo

Comments