In recent years, more women are entering the sake business including in the role of toji (brewmaster), yet the rarity of women in the male dominated world of brewing still makes news as a Sake Times article in 2021 by Jim Rion describes. In medieval Japan (1200-1600), women played a much more prominent role in the sake business than today. In fact, the term toji is thought to derive from the ancient word meaning female clan leader.

The First Toji Was a Woman

When the word toji appeared in the eighth century, it referred to a female chief of a provincial social and economic unit called a gōzoku (clan). Only women were toji as the male chief was called obito. More than simply the spouse of the clan head, the toji held authority over the clan.

By the ninth century, the usage of toji expanded and the meaning changed to refer to the female head of a wealthy household. In other words, although the term became more widespread, the authority of the toji diminished since the title now meant wife. However, the toji continued to have important duties such as brewing sake. One story in the eighth-century collection of Buddhist tales, Record of Miraculous Events in Japan (Nihon ryōiki), describes an impoverished woman who prays to the Bodhisattva Kannon for help finding a wealthy husband. Through the divinity’s intervention, she is wed, and her spouse provides her with gifts befitting her new status as toji. She receives cloth to make better clothes for herself and rice to brew sake.

The sake made in the story was probably for home consumption, but many medieval brewers were mom and pop operations in which the entire family was involved in sake production, not just the men. A typical medieval brewery relied on dozens if not hundreds of ceramic vessels of one koku (45 gallon) capacity to brew sake in small batches year-round. In the early fifteenth century, 347 breweries operated in Kyoto. We can know the number of breweries thanks to lists compiled by the capital’s koji makers. One such list dating from 1425 shows three breweries owned by women. Women likely assisted in the operation of other breweries too even though the ownership of the breweries would have been listed under their husbands’ names.

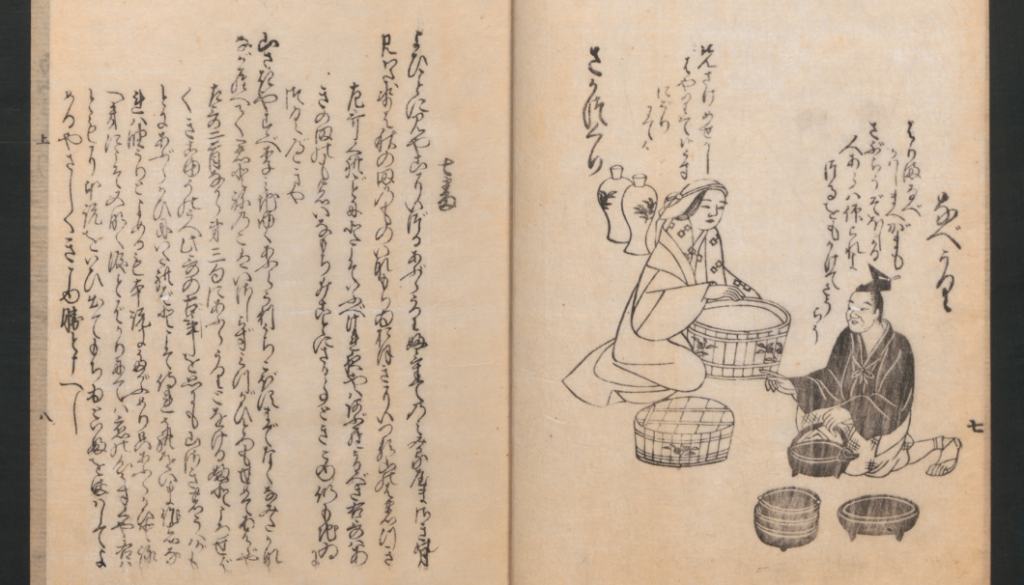

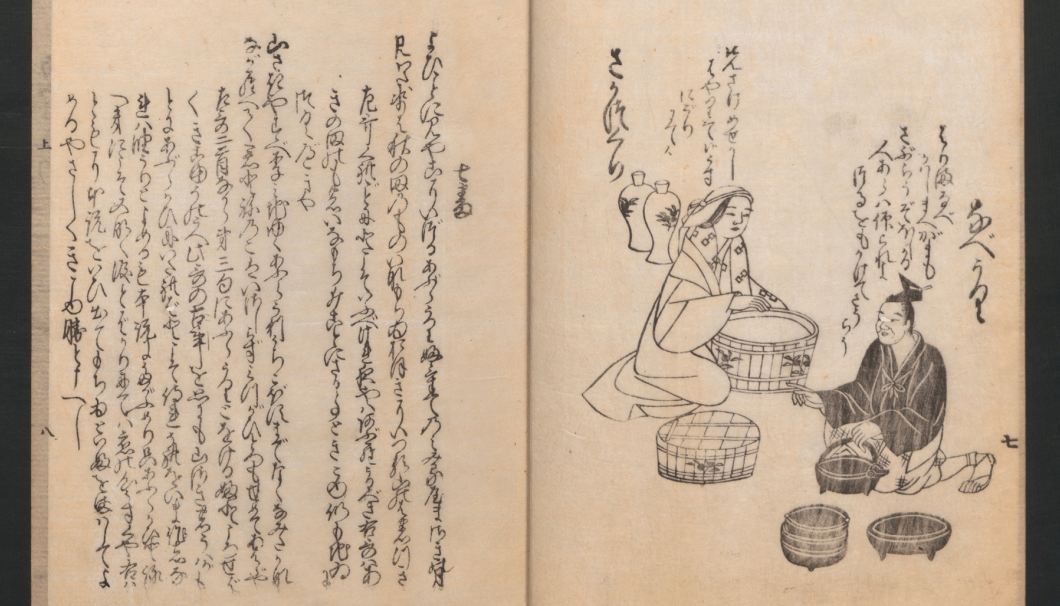

The prominence of women brewers is evidenced in a picture scroll dated to 1500, Poetry Competition of Seventy-One Artisans (Shichijū ichiban shokunin uta’awase). The painting depicts 142 tradespeople with accompanying poems, and the sake-maker is a woman. Pictured next to a pot seller, the caption above the sake maker reads: “Try my sake, and I have the popular usunigori too.” One of the sake maker’s containers is open, allowing customers to see the usunigori, a sake clarified when the lees (kasu) have naturally settled to the bottom. Usunigori (also called nakagumi) would have fetched a higher price than cloudy nigori since it was more refined. However, the sake maker’s real prize is in the decorated containers behind her, which likely hold a higher grade of sake, perhaps koshu, sake aged upwards of ten years that wealthy customers preferred in that period. The same collection of Buddhist tales mentioned earlier contained another story meant to serve as a warning to women who sold sake that if they diluted their brews too much with water, they would go to hell for it.

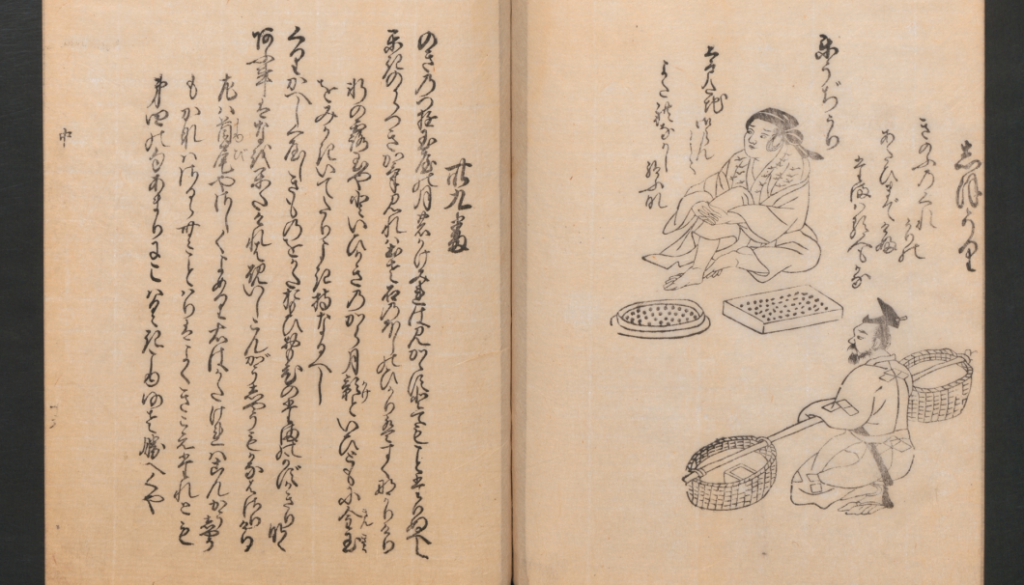

Poetry Competition of Seventy-One Artisans further reveals that women were involved in the koji trade. The medieval shogunate prohibited sake brewers in Kyoto from making their own koji, so they instead had to purchase koji from the official guild affiliated with the area’s Kitano Tenmangu Shrine. Brewers who violated the ruling risked having their operations destroyed.

The caption above the koji seller reads: “Sake drinkers look, but please don’t drool.” Though koji is a key ingredient for making soy sauce, miso, and medieval versions of sushi, the koji seller depicted in the scroll (below) is shown calling directly to sake consumers and by extension brewers via the caption, suggesting that they are her main customers. Judging by the image, her koji is not in powdered form (tane koji) but rather already inoculating rice allowing buyers to use it immediately for sake making.

How Technological Changes Affected Women

The art of brewing changed considerably in the transition from the medieval to the early modern period (1600-1868) and that diminished the place of women in the sake business. Brewers abandoned using one-koku ceramic vessels in favor of wooden barrels with much larger capacities initially up to ten koku, which allowed them to increase production. Ramping up production created a need for more workers, and the shift away from brewing year-round to winter sake making meant these new employees could be seasonal staff. The laborers who were available were male farmers and fishermen seeking employment in the off-season. Typically, workers from the same rural areas would return to the same breweries every year where they would live for several months while brewing sake. Over time, these laborers organized guilds with masters called toji who became responsible for all aspects of sake brewing. Women in the households of families that owned breweries probably continued to have an auxiliary role in sake production in the early modern period, but as sake brewing grew in scale the increased physical labor needed in the brewery became the sole domain of male seasonal workers.

Women continued to brew sake at home up through the twentieth century (and probably illegally in Japan today), but after the seventeenth century, the title toji referred to the master brewer, who until only very recently, was always a man.

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments