Made from water, rice, koji and yeast, sake might appear at first glance to be obviously vegan, but it turns out that part of the manufacturing process might include unexpected animal products. SAKETIMES talked to important members of the industry to clarify how this might be, and what is changing in the world of vegan sake.

Sake: Vegan or Not?

Basically, sake is made from purely plant-derived ingredients. Even the brewer’s alcohol added to non-junmai sake is distilled from plants – usually sugar cane waste, molasses or corn – so sake should be a vegan drink. There is, however, one sake-making step some breweries use that can change that.

Sake is relatively clear after pressing, but over time leftover proteins can clump together and create cloudiness — called turbidity in the drinks industry. There are many ways to prevent turbidity, but for large scale brewing the most cost effective way is through chemical finings, or orisagezai in Japanese. Conventional orisagezai combines gelatin made from pork or beef byproducts to attach to the proteins, and persimmon tannins that then clump the gelatin so it precipitates naturally for easier removal. According to representatives from vegan certification non-profit Vege Project Japan, this is the one step that could prevent any given sake from being vegan.

Vege Project Japan certifies consumer goods as vegan, they say, to promote a society that is more open to vegan and vegetarian issues. Founder and director Haruko Kawano and intern Takami Li spoke to SAKETIMES about their certification process for sake.

“In principle, we check only ingredients that go into the final product,” explains Kawano. “For sake, we ask for documentation of the ingredients list, and if they do not use gelatin based finings, then we approve the sake.”

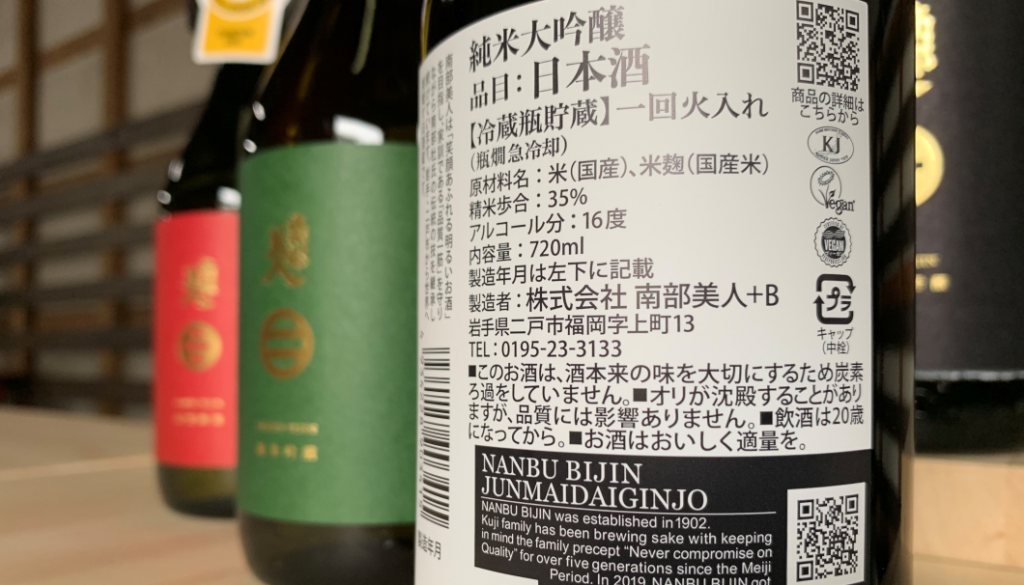

Since there are no international standards for vegan certification, Li states that it is vital that certification organizations be clear about their standards and limitations. Vege Project Japan makes it clear that they only certify individual products, and only based on their direct ingredients. Secondary elements that do not go directly into the product – equipment, labeling, and so on – aren’t included in the evaluation. Currently, Vege Project has certified products for 20 sake breweries. The very first brewery to get full vegan certification for all products was Nanbu Bijin, in 2018, but major brewery Hakutsuru took big steps in that direction as early as 2001.

Alternatives to Gelatin

Many small breweries abandoned finings long ago, because they either ignore the issue of turbidity altogether, or use other methods to solve the problem. These include using a physical filter with an ultra fine-grained mesh, or paper to remove the proteins. For larger-scale breweries, though, turbidity is a quality issue that needs addressing.

Hyogo Prefecture’s Hakutsuru, one of the largest sake breweries in the world, still uses finings for many of its low-cost futsu-shu products. However, the spread of mad cow disease in the early 2000s encouraged the brewer to eliminate animal products out of safety concerns.

“We worked with manufacturers to investigate non-gelatin finings that would not impact quality, and came up with two different solutions,” reports production representative Hitoshi Mitsutani. “One uses persimmon tannins with seaweed-derived sodium alginate to replace the gelatin, and the other uses sodium alginate with silicon dioxide.” The different chemicals require careful balancing of ratios to avoid impacting flavor or aroma, so it took a year of experimentation to get the mix right, the brewery says.

Now, Sakurai says that Hakutsuru is completely animal product-free, although the label might not indicate it. “We have some vegan-certified products in international markets,” adds Kazumasa Sakurai, another member of the Hakutsuru production team, “but certification is handled purely on a market-by-market basis.”

Companies must balance the cost of certification, which has to be renewed on a yearly basis, against the benefit of possible increased sales. For vegan sake pioneer Nanbu Bijin, though, the benefit goes beyond sales.

Making the Truth Obvious

Kosuke Kuji, kuramoto owner and manager of Nanbu Bijin, told SAKETIMES, “It’s simply the truth that, at heart, sake is a vegan product. All we did was make that obvious.”

Kuji initially got kosher certification for his sake in 2013 as a way to show that his sake was a viable choice for consumers with religious dietary constraints. “When I did that, people started to ask why we didn’t apply for vegan certification, as well.” Since kosher certification also checks for animal products that might violate its rules, it seemed like an obvious next step.

“We never even used orisagezai,” explains Kuji. “We didn’t have to do anything different, just show people what we were already doing.”

This is what he finds to be most important. “Sake is, and always has been, this way. Orisagezai use only came about during the kyubetsu seido to get first class qualification. Most small breweries don’t do it, anyway.”

The kyubetsu seido was a sake classification system used from 1940 to 1992 that classified sake into one of three grades based on taste and appearance. The reliance on appearance encouraged breweries to find ways to reduce sake’s natural turbidity. Traditional methods like oribiki – storing the sake in tanks for extended periods to let the proteins settle, then racking the sake off the top – took time and led to some risk of degradation for premium products aimed at top class certification, so chemical alternatives appeared. Now, though, the industry and thought process have changed.

“I don’t know of any small breweries that still use orisagezai,” says Kuji. “I want every sake brewery to think about getting vegan certification, so we can show people what sake really is: a pure, healthy, and safe drink that is open to everyone.”

A Vegan Future for Sake?

Although some breweries still do use gelatin finings – Li from Vege Project says that there have been breweries that applied for certification but failed because they didn’t realize themselves that they used gelatin – the trend away from it seems clear.

“We are seeing more and more breweries apply for certification,” Li adds. Shuso Imada, General Manager of Japan Sake and Shochu Brewers Association Information Center, indicates that while there is no central record of how many breweries use finings, the general sense is that “using gelatin finings is becoming less and less popular among the breweries.”

As Kuji says, some 10% of the global population is vegan. That’s a lot of people, and he feels they should be able to pick up a bottle of sake with confidence.

“We want to demonstrate that sake is an option for people who have made that choice,” he says. As more breweries join his way of thinking, the options for consumers will only grow.

Top image: Photo by ja ma on Unsplash

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments