Iwa 5, a blended sake from former Dom Perignon cellarmaster Richard Geoffroy, and bespoke sake maker Tanaka 1789 x Chartier’s products, produced with the help of famed wine sommelier Francois Chartier, have proven big hits in the sake world and have recently put a spotlight on the concept of blending sake to create new flavors. Blending sake, though, is nothing new. It’s a practice that goes back centuries and forms the backbone of some of today’s most popular labels.

Edo Period Blenders

The modern sake industry is in many ways rooted in the Edo Period (1603-1868), when sake left temples and shrines to become a general consumer product. Breweries all over the country sent their sake to the new capital at Edo (present-day Tokyo) to satisfy the voracious appetites of the newly urbanized area’s populace.

Shuji Horie, sake historian and former technical instructor at the Shimane Prefecture Institute of Industrial Science & Technology, tells SAKETIMES, “Sake sellers in Edo would get sake from makers all over the country and blend them for sale.” The goal, he says, was adjusting flavor to match customer needs. Sake of the day was extremely sweet, Horie explains, and with the varying tastes of people gathering from all over Japan, Edo’s sake sellers would blend sake to match a wider range of preferences.

One of the breweries sending sake to Edo was Kenbishi, which is still in operation. President Masataka Shirakashi says that the company still keeps records from the time. These records state that brewers would blend sake themselves before sending it to the capital.

“Back then, aged sake sold for more than fresh, so Kenbishi’s toji brewmaster would blend mature brews with fresh to expand the stock,” Shirakashi explains, “but it also created complexity in the sake. With all those different people gathering in Edo, the cuisine was also varied, and blended sake was more versatile.”

Naturally, sake blending didn’t end in the Edo period, but has remained fundamental to the industry to the present day.

Finding Flavor

The most common role of blending in modern sake brewing appears to be to create a stable flavor profile. Jun Kono, president of Tochigi Prefecture’s Sohomare Sake Brewery, is another prominent modern sake blender.

“Our blending started with futsushu,” he says. Futsushu is the most common class of sake, covering everything that falls outside the premium tokutei-meisho-shu designation and often considered the equivalent of table wine, so it needs stable, predictable quality year round. “We made batches of sake with no. 7 yeast and no. 9 yeast and blended them to make our futsushu.”

Kono insists that this was commonplace when he first joined the industry, giving the example of a popular Niigata-based brand in the 1990s. “I toured the brewery, and learned that they mixed no. 7 and no. 9 in their futsushu, too. I think lots of breweries did the same.”

They did not simply mix two full tanks, though. “Some really irresponsible breweries might have just thrown things together,” he laughs, but the ones worried about flavor would work out the best ratio during regular tastings that breweries hold to monitor how flavor has developed, and to ensure the quality of their product for the year.

Horie reports that blending sake made from different yeasts is perhaps the most common example in the industry. “There are many new yeast strains that make very aromatic sake, but the brewery might not want such powerful aromas, particularly for meal sake. So, they will use no. 7 for one batch and mix it with a more modern yeast sake to make something more balanced.”

For premium sake, though, blending becomes more complex. Kono explains that Sohomare ginjo has also been a blend since his father’s days in the industry. “We used to make different batches of ginjo for competition, store them in 1.8 liter bottles, then blend based on tasting results to get the best result,” he recalls. In this case, he says, the differences were less about how they made the different batches than in how they had matured in the bottle, and those deviations can only be judged by tasting.

Master Palates

Blending in sake is not only a long-established practice, but one that hinges on the palate of a key individual in much the same way that wine blending does.

Kono himself is in charge of the blending team at Sohomare, and the process has evolved under his direction. “In general, we keep stock of premium sake aged one year, two years, and three years,” Kono explains. The sake comes from different batches using no. 6, no. 601, no. 7, and no. 1401 yeasts.

“For example, we will make batches of kimoto junmai daiginjo and age them in 1.8 liter bottles. Then, when it comes time to ship our team will bring in some two year-old made with no. 6, some two year-old made with no. 7, and so on. We use at least ten different batches at different ages, taste them, then decide which ones we will blend together at what ratios.”

The differences in how similar sake ages is a key element in Kenbishi’s blending, as well. Kenbishi’s President Shirakashi tells SAKETIMES that all of the brewery’s products except for the Nada no Ki-Ippon label are blended.

“We have three base sake styles: a honjozo made from non-Yamadanishiki rice, an Aiyama honjozo, and a Yamadanishiki junmai.”

The last is what goes into Nada no Ki-Ippon. All of Kenbishi’s sake is aged, and the finished products are blends of different batches aged for different amounts of time. Shirakashi gave the example of the brewery’s premium labels Mizuho and Zuisho: “All of the sake that goes into Mizuho has aged at least ten years, while everything in Zuisho is at least fifteen years old,” he says.

Shirakashi can’t give any specific ages or ratios, though, because sake maturation is wildly variable. “We taste all of the batches each year, and decide the ratio based on flavor progression. One year the 12-year-old might be really good, while the next year it might have dropped off.” The flavor comes and goes in a wave, he explains.

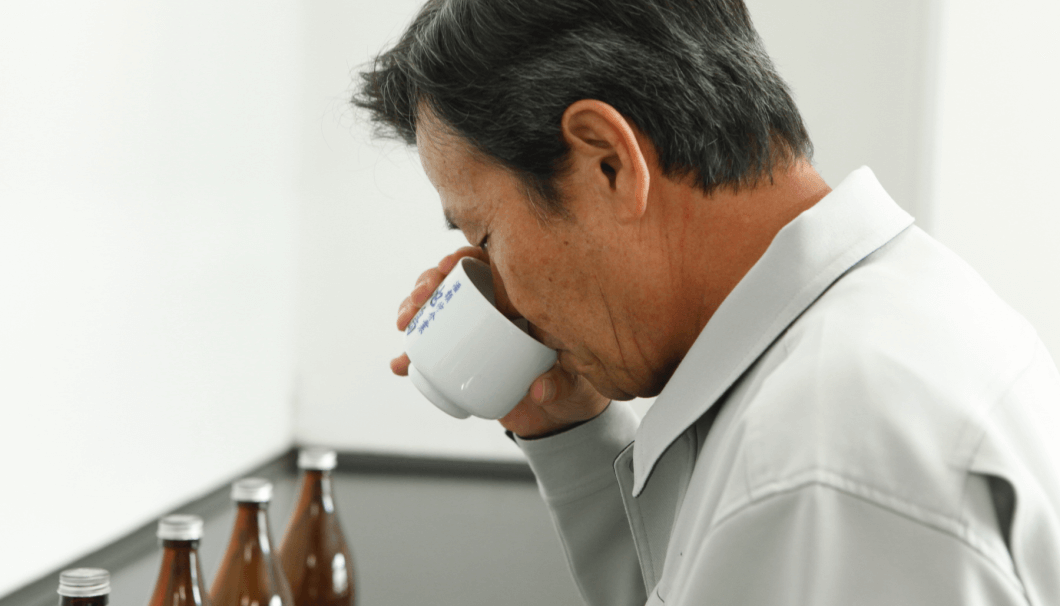

Kenbishi employs a head blender who manages the sake after fermentation is complete, and monitors flavor progression as the sake ages, then offers up proposals for ratios to go into each product. The final decision falls to a quality assurance team that Shirakashi heads up, though.

“It all comes down to my palate,” he says, and he is also key in choosing Kenbishi’s head blender. He explains that he speaks with key staff members about potential blenders, then checks their palates himself. Promising staff are sent to tasting seminars run by the National Research Institute of Brewing, but after that all training is in-house.

Out of the Shadows

Blending is not nearly as public in sake as it is in wine, though. Sohomare’s Kono believes that’s because it’s simply too common. “It was just a basic part of each brewery’s process that it wasn’t worth talking about,” he says.

Horie, however, thinks that part of the reason is a natural reticence by brewers to talk about their technique. “For some reason, sake brewers don’t like to share what they do. Maybe they don’t want people to copy them,” he offers. Whatever the reason for the past silence, it’s been broken now.

The two French wine-influenced sake blends mentioned at the top of this article are only the tip of the iceberg. In recent years, sake breweries all over have collaborated to and release totally new blended versions of their products. For example, KKB Blend is a label overseen by sake sommelier Koichi Kudo that’s made with three different blends of two Akita Prefecture breweries’ sake: Chitosezakari and Akita Kinmon.

The pandemic also drove a spate of blends as breweries took to blending to drive sales of backed up stock. Six breweries in and around Hagi City in Yamaguchi Prefecture teamed up to make Corona ni Makeruna for two years running, while Niigata Prefecture’s Ayumasamune and Chiyonohikari teamed up earlier this year to release a blend called “Nihon no, Osake Chiyoayu.”

Right now, at the end of 2021, six breweries spread all over Japan are cooperating in a major project on Japanese crowd-funding site Makuake that they call a “sake blending relay,” as they take turns blending their sake to create different expressions.

It’s clear that sake blending has stepped out of the shadows and is taking a more public role in sake. We can only wait and see what new sake gets mixed up next!

*Top image: Photo by Kenbishi Sake Brewing

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments