With her inclusion on the BBC’s 100 Women list in 2020, Miho Imada has cemented her status as one of sake’s most pivotal figures.

The list highlights inspiring and influential women from around the globe, including luminaries from the fields of art, medicine, sport, poverty relief and equality.

Imada has gone on to attract widespread media attention both domestically and overseas, not only for her role as one of Japan’s rare female brewmasters, but also for her commitment to the craft of sake brewing. This dedication stems from the sake culture of Imada’s home prefecture of Hiroshima, Japan and her sense of responsibility as a regional sake brewer.

The road to international recognition

Overlooking Japan’s picturesque Inland Sea, the fishing village of Akitsu, Hiroshima, has a deep-rooted culture of sake brewing. This tranquil hamlet is home to Imada Sake Brewery, founded in 1868, a brewery long famed for its Fukucho Ginjo — a fine pairing sake with a subtle and delicate flavor.

Due to this unexpected recognition, Imada suddenly found herself thrust into the spotlight. She was featured in an article in The Guardian and was inundated with interview requests from media outlets across the world.

“One Columbian journalist who interviewed me was very knowledgeable about gender issues. I had never spoken to anyone like that before, so the meeting made a strong impression on me. I can’t really say what effect all this had on our sales, but we started to get more inquiries from Europe, even during the coronavirus pandemic. It also helped during business negotiations, so there were definitely some positive results.”

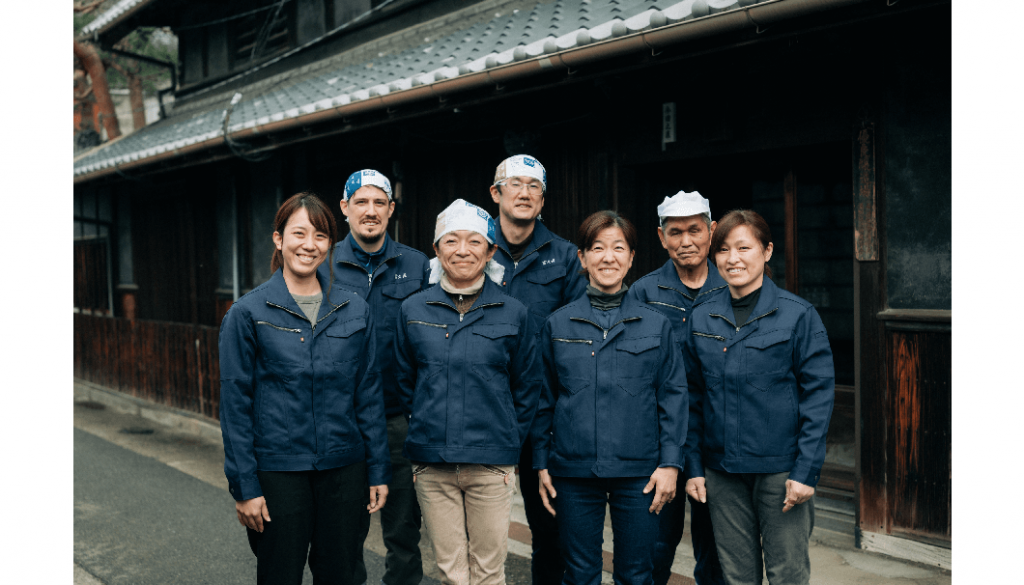

United as brewers

The eldest daughter of five siblings, Imada never planned to take over the family brewery. She left home and moved to Tokyo for university, then spent 10 years working there during the mid-1980s. During that time, she took on a number of jobs in the cultural sphere, including event organization at a department store and working in Japan’s traditional Noh theater.

The turning point in her life came at the beginning of the 1990s. Her only male sibling decided to become a doctor, leaving Imada Sake Brewery without an heir.

“A string of coincidences led to my decision to return home,” says Imada. Although she had the option to work on the managerial side of the brewery, Imada chose a more hands-on role.

“Up until that point I had worked behind the scenes in the art world, organizing exhibitions and producing theatre. This felt like my once-in-a-lifetime chance to finally take center stage as a creative.”

At that time, the Japanese sake industry was undergoing a seismic change with the abolition of the old tier-based categorization system. In addition, the relaxation of sake retail regulations led to the dominance of large discount stores, sowing doubt about the future of regional breweries and independent sake stores.

“I drank a lot of good sake in Tokyo,” says Imada. “And I realized that to succeed as a business we would have to compete on quality. But as a sake novice, I had no idea how long it would take to convince my father and the head brewer to change their approach. It seemed the best option was simply to do it myself.”

There had been female brewmasters in Hiroshima Prefecture before, so Imada’s goal may not have seemed completely unfeasible.

“In Hiroshima, head brewers put a lot of emphasis on their staff. The brewers are not just seasonal laborers who come in from another prefecture; they have roots in the local area, and this means they develop expertise. There is a feeling that we are all ‘brewing partners.’ Our skills are for the benefit of the group, not just oneself. The brewers improve by teaching their skills to each other, which creates a culture of information sharing. There are elements of feudal hierarchy, but with a logic to it, and workers with motivation and skill are properly valued.”

Asked about her struggle to succeed as a female brewer, Imada is forthright: “People often say it must be hard being a woman in that environment, but the biggest difficulty by far is simply making it as a brewer.”

Finding universal appeal by aiming locally

Since Imada became a brewer at the age of 33, she has sought to improve her brewery’s sake in a way that reflects the local character of her region. One aspect of this has been her focus on Hattanso, a Hiroshima sake rice variety once considered lost.

“About 150 years ago, there was no distinction between sake rice and cooking rice,” explains Imada. “Among the native varieties of rice, Hattanso is relatively easy to polish thanks to its large grains, making it suitable for sake brewing. But it also suffers from a low yield and falls over easily due to the height of the plant. In the process of trying to cultivate an improved strain, farmers eventually stopped growing Hattanso altogether.

“Because it is a natural strain, Hattanso has a hard grain and cannot be brewed using the same methods as Yamadanishiki or other rice cultivars created through selective breeding. But at the same time, it has its own interesting characteristics that are clearly reflected in the sake.”

Imada Sake Brewery combines Hattanso rice with a sake brewing method suitable for the local soft water, developed by the Hiroshima brewmaster Senzaburo Miura in the Meiji Period (1868-1912). But while the materials and techniques are important, Imada also aims to reflect the character of her locality.

“A sake’s flavor reflects the sensibility of a region and its people. This takes multiple generations to develop. The best compliment a brewer can receive is to be told that their sake has depth, meaning delicate umami, smooth texture and a beautiful aroma — a sake you can drink every day and never tire of.”

“Akitsu is located on the coastline of the Inland Sea, a temperate area with no snowfall. Fresh food is available here all year round. When people eat a variety of fresh seasonal produce without the need for strong flavorings, they grow sensitive to these subtle flavors. To appeal to people like this, you have to make a well-balanced sake that draws out the goodness of its ingredients.”

By aiming to impress locally, Imada created a sake with universal appeal. And although her brewery offers a wide range of products, each sake they make is infused with this same basic philosophy.

Innovative techniques lead to new flavors

As part of their mission to express the authentic flavors of Hiroshima, Imada Sake Brewery uses a state-of-the-art rice polishing machine developed by Satake, a company with roots in the local area.

“People often say that rice and water quality are the reasons why Nada in Hyogo became such a famous sake region,” says Imada. “But the key factor was actually the water wheels used for rice polishing. These were powered by river water from Mount Rokkō. There aren’t any large rivers in Hiroshima Prefecture, so it isn’t possible to power water wheels with hydro energy. That is why Satake developed the first electric rice polishing machine for sake.”

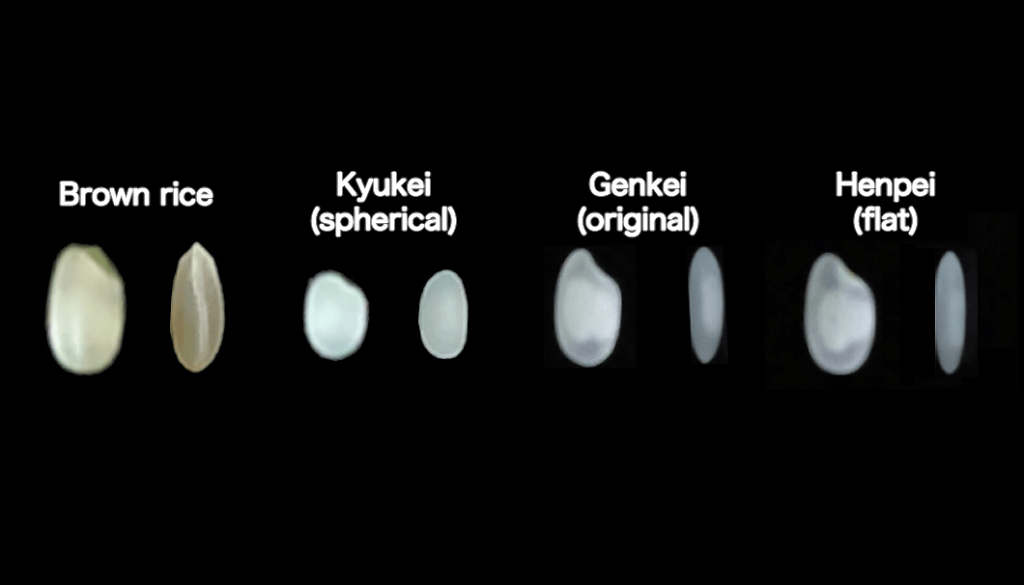

Satake, now a global manufacturer of food processing machinery, returned to their roots to support the local sake industry. They developed two revolutionary new methods of rice polishing: henpei (flat polishing) and genkei (original form polishing).

“During the ginjo boom in the eighties and nineties, breweries competed with each other to push rice polishing to its limits. This led to a dead end. We were concerned by this trend, but luckily Satake showed us an alternative to simply focusing on polishing ratios. They gave us a new lease on life by demonstrating the potential of polishing techniques, not just polishing degrees.”

With henpei rice polishing, it’s possible to remove the same amount of protein by polishing to 60% as it would be by polishing the rice to 40% using a more standard spherical polishing method. And while henpei rice and genkei rice contain roughly the same nutrients, their different shapes result in wildly different flavors.

“There are still a lot of things we need to experiment with,” enthuses Imada. “Whether it be the use of koji rice, adding brewing rice, or how the rice reacts with the yeast.”

Imada now has her sights set on a new project: Imada Sake Brewery’s Fukucho Legacy series of matured sake.

Imada recalls that some international consumers she’s spoken with prefer complexity in their drinks. “It seems odd to them that sake prides itself on clarity,” she says, noting that, in Japan at least, white wine is seen as sake’s closest competitor. “I think we can produce a sake that could even give red wine a run for its money,” she concludes.

“I tried to find a way to layer complexity on top of clarity, and the result was Fukucho Legacy. If we can increase the food pairing possibilities for sake, the field will widen and the number of players will increase. That’s why I think it’s a good idea to switch things up by changing the rice polishing method or dabbling in vintages. There’s no point in a technique if it isn’t evolving with the times.”

Stepping outside the framework established by her gender, Imada has devoted her life to improving as a brewer. In a traditional sake industry frequently bound by custom, she has forged her own path forward, providing inspiration to women all over the world.

*Translated by D. W. Lanark

*If you would like us to send you monthly updates and information, register here.

Comments